On the bus a Belgian guy sits next to me. Perched on his hipbone sits a Nepalese woman, on her sits a small child. And in front of us sits a scarfed goddess wrapped in red pashmina. This was the first time myself and Pieter, the Belgian, had been outside of Europe. We soon approach Besisahar, the gateway to the Annapurna Circuit.

The bus came to an abrupt halt at around noon. Pieter and I take a bridge out of town disappearing into the hills. We soon relax into an agreeable pace, deciding two heads are better than one. The pace increases, sinking into our fresh legs for the next six hours.

The sun was giving up on the day. The smell of earth cut through the clay dust that covered us head to toe. Static raised hairs on our necks and the sky was turning ominous. The tractor we had hitched disappeared in the direction it had come from. We were standing in the porch of a roadside shack. Rain was closing in. It was time to find shelter and rest our heads.

The smell of earth cut through the clay dust that covered us head to toe. Static raised hairs on our necks and the sky was turning ominous.

That night a storm hit. I awoke in a concrete fortress to the sound of white noise and slamming doors. A veiled woman watched me sleep through the window above my head. I look across the room to an empty bed. The woman was still there. Exhausted I shut my tired eyes and curl into the quilts of my cheap Chinese bag.

In the middle of the night three girls of different nationalities, including their guide and porter take shelter in the guesthouse. They were riding in a jeep heading to Chame, a two-day walk away. The jeeps axle had given up, leading them to abandon the vehicle and find shelter from the storm. We joined paths by coincidence, or through the fate of poorly made parts and a walking pace that would likely cause trouble for Pieter and I in the proceeding days. After we caught sight of them in monsoon rain mid morning, I was happy that two had become a band of seven. A harbor amongst what was proving to be the most relentless rain I had ever seen.

The smell of earth cut through the clay dust that covered us head to toe. Static raised hairs on our necks and the sky was turning ominous.

The landscape changed dramatically as we pushed further into the jaws of the Marsyangdi Valley. Everything accentuated. The river seemed to have split the valley this very day. Displaying its power as we straddle a slippery path in the sky. Praying for the cliffs to hold, we watch jeeps duel on the crumbling road ahead.

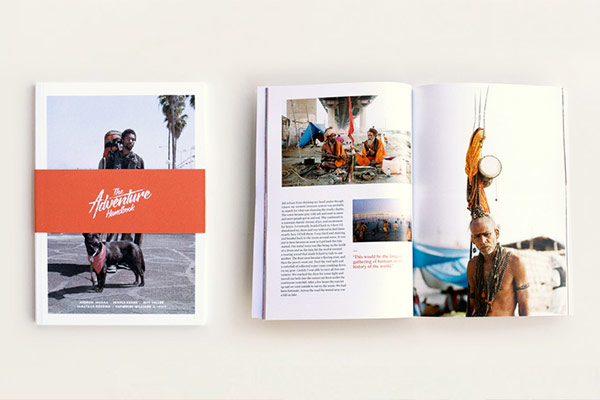

The girls Nepalese guide Keshar is from a remote mountain village in the Solukhumbu district. Situated in northeast Nepal, he’s Sherpa by caste and has been a guide for the last ten years. Like most guides in Nepal, Keshar began his apprentice as a porter. He learnt his trade just like Tek. Tek is a silhouette in the mist ahead carrying sixty kilos of luggage in flip-flops. He lives in Kathmandu with his young family, mother and siblings. Supporting them through porter work when he can get it, and by sewing jeans in the off-season.

As I wake from Dal Bhat dreams, I find myself lying on a plank of wood between Pieter and an American girl named Jamie. In the damp room I notice the rain has stopped. I can see blue sky through the moldy curtains. I walk up some steps barefoot to the rooftop where I brush my teeth and look at the first view of a snowcapped peak. The blinding unknown peak stays embossed on my retina for the next five minutes as I try and locate my drying clothes.

The blinding unknown peak stays embossed on my retina for the next five minutes as I try and locate my drying clothes.

‘Life is damaged’ Keshar whispers as he smiles, exhaling thick smoke from his last Nepali cigarette. He spends the most part of the year away from his family. Scraping together enough rupees during the short trekking season to put his three children in school. Work is never certain. Conditions are tough. There is little compensation should an accident happen.

Steam is rising from our damp shirts as we emerge from heavy waterfalls and fields of marijuana. Spirits are bathed in unfiltered rays as we acclimatise to the thin air.

I don’t know how many days have passed until the phone call. It’s mid day and salt is forming contours around the napes of our baselayers. As we approach a water stop Keshar passes his Nokia to Jamie. It’s her brother calling from the States with some news. It’s been reported on CNN that over three hundred trekkers are missing on the Annapurna Circuit.

It’s her brother calling from the States with some news. It’s been reported on CNN that over three hundred trekkers are missing on the Annapurna Circuit.

Days later, the mood has changed. We continue upwards, thinking about the storm we had walked through, and the devastation it had caused above. Individuals are locked in thought. Trapped In long stares, the dry wind burns our glassy eyes. Helicopter activity is increasing. People are steadily descending. We negotiate the remains of an ice avalanche two stories high, peppered with trees and boulders. Pieter tends to a distressed porter. Whilst unloading a helicopter, fragments of ice hit his eyes. Temporarily blinded his boss tells him to hurry up.

In the distance an airstrip glimmers in the blazing afternoon heat, it looks around five miles away. We tread through snow amongst ancient trees passing men on horses. This is the Manang district. As we approach the town of Humde, a little girl stands in the road welcoming us to her teahouse. Amongst our group is Sumi, a Nepalese girl who studied at MIT and works in America. She laughs and plays with the little girl as we eat. Speaking to her in Nepalese, Bipana tells Sumi her story. Later that day I find out Bipana was sold to the owner of the teahouse to work as a waitress at eleven years old. After resting a while we prepare to leave for Manang. The little girl asks Sumi to stay.

Keshar explains he has never seen snow touch these parts at this time of the year. We each hand over our permits at a police checkpoint. Assured there is no danger in Manang, we press on. Moments later we are spinning prayer wheels in an amphitheater of six thousand meter peaks. Three Annapurna’s and Khatung Kang, a black tooth standing proud in the distance. Each mountain balancing buildings of snow on shelves and shoulders, exposing heavy slabs in the strong October sunlight.

As we settle in Manang at 3520m the routine becomes natural. We start a fire, fill the room with smoke and chew the fat till our eyes itch. It’s through these nights that we’ve gotten to know Keshar and Tek. Porters aren’t usually persuaded to mix with their customers; his other boss doesn’t allow it. It’s common for them to do their job and disappear. Tek opens up. He’s dancing Nepali style with Keshar and friends to a mountain song. I can smell Roxy in the air. They’ve just visited Keshar’s uncle. He’s lucky to be alive having been caught on Thorung Pass during the blizzard. His horses lead him to safety. Tek’s smile is infectious. Little do we know his brother is missing in the area.

His horses lead him to safety. Tek’s smile is infectious. Little do we know his brother is missing in the area.

I wake at six am and take a cold shower. The clay floor quickly disappears under a black pool of water. I creak upstairs and make the small transition outside. The cold mountain air slaps my burnt face as I look at Gangapurna and its steep glacier. I hear a crack followed by an echoing boom. An avalanche thunders down the icefall smashing into a wave of powder.

The stories are haunting. If you continue up the main valley you’d soon reach a fork. If you were to take the route to the west you’d find yourself winding up a barren scree slope. This path takes you to Tilicho Base Camp, and further to Tilicho Lake. Rumors have it there were people trapped in the lodge there, contained by five feet of snow. If you take the fork north you’re a two-day walk from Thorong Pass, the highest pass in the World. The epicenter of the tragedy we knew very little about, and what seemed like the edge of the world.

It’s just gone five p.m. The surrounding summits are bathed in creamy light. I’m sitting on the edge of an Ice lake looking up at its source, frozen in breathless silence. A fox stops in its tracks, its wide eyes reflect in the beam of my head torch. By now information has reached that the army has closed the pass. It’s time to head down. We prepare to leave in the morning.

With their backs to Manang, Pieter and Sumi tail off our group. Retracing their footprints down the valley through familiar villages. The air is cold and still as they tread through burnt autumn leaves. They are alone in rugged wilderness until they hear something approaching from behind. Through the dust emerges the little girl. Sumi drops her pack and catches Bipana in her arms.

They are alone in rugged wilderness until they hear something approaching from behind. Through the dust emerges the little girl. Sumi drops her pack and catches Bipana in her arms.

On the night of October 13th, Nepal was hit by the tail end of a dying tropical cyclone. In the proceeding days 39 people comprising of tourists, porters, guides and locals lost their lives. This is the worst trekking disaster in Nepal’s history.

Words and images by Rob Turner.

Receive a postcard from us sign up