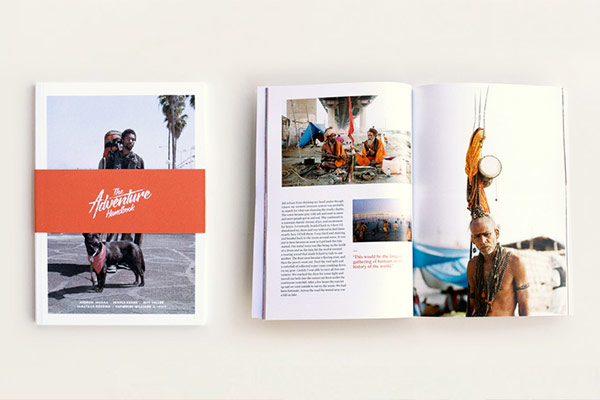

Théo de Gueltzl started his journey one year and a half ago in Los Angeles. He bought a Toyota Pick Up, built a wooden structure to fit a mattress and a life on the road. Bulking up on nuts and sardines he started his trip going south. He spent some months in Baja California, Mexico, where he met his dog Puca on the beach, traveling with her ever since. Together they drove through Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, Cuba, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, until Panama. There he shipped his car across the Panama Canal to Cartagena in Colombia, drove it to the desert of Colombia, pierced a tire and finally settled in Bogota. Staying here for a year, he will be spending his days working at his metal workshop, atelier and continue doing photo reports.

I’ve listened to so many people telling me their dream of traveling, of exploring the world, of escaping their daily routine. It happens too fast that one gets stuck in their own life. Your dreams are held back by financial responsibilities, may it be the mortgage payments of your home, the aftershock of a divorce, or simply the fact that you have to pay rent. The irony is that we get wrapped up in these financial responsibilities because we follow the dream image of modern society. To buy the house you always wanted, to maintain a high standard of living, to support your family etc. you need financial wealth – you’ll basically work until you’re retired. I feel like these mechanisms of society prevent us from following our individual dreams, which exceed having a pretty house and a successful career.

Even the camping type of traveling has become a major business. The free spirit of travellers has become a big selling point for companies, advertising their products and polishing up their image with the “free”, or “back to nature” lifestyle.

Naturally, people keep having those dreams. Which makes it easy for companies to create materialistic needs off these dreams. You’re unhappy? Why not buy this and that or maybe taking a week holiday? Traveling, which in my eyes means escaping our society, therefore has become some sort of luxury. Even the camping type of traveling has become a major business. The free spirit of travellers has become a big selling point for companies, advertising their products and polishing up their image with the “free”, or “back to nature” lifestyle. It’s a similar story with the hype of organic products. Something that should be the most basic good, natural produce has become an extravagance.

It’s often only once you’ve left your comfort zone that you realise what you’re really passionate for. There you start to realise what you really like, instead of what your parents or the society has foreseen for you.

Another factor in the relation between needs and dreams is the security net provided by society. It reaches from financial security to physical security and safety. Many people are scared of traveling into foreign countries. We tend to have presumed ideas of certain places and of what could happen to us. The unknown scares us, and often a lack of experience lends to prejudices and presumptions that we came across in our life. We naturally feel more comfortable in familiar environments – we know what to expect. I think that’s why franchise works so well. People rather go to a Starbucks or a McDonalds in a foreign country, simply because it gives them a certain feeling of familiarity. And I’m not just speaking about safe Europe. Prejudices and xenophobia are global phenomenon: while crossing Central America, the people of each country were the most scared of their neighbouring country. For people in Belize the inhabitants of Guatemala were criminals, in Panama, going to Columbia was considered as unimaginably dangerous.

I always try to steer from comfort in my artistic practice as well. It’s easy to do the things you’re good at, the things you know that will please your audience. But you won’t move from the spot. I take challenges as part of the creative process. I try to find a new method or technique, that’s foreign to me, in order to learn, to experiment, to make mistakes. Those mistakes are then unique to yourself: you do things differently and these mistakes become a way to define yourself.

It’s often only once you’ve left your comfort zone that you realise what you’re really passionate for. There you start to realise what you really like, instead of what your parents or the society has foreseen for you. The longer you wait, the harder it will be to change your comfort, your standard of living.

Traveling is one of the biggest life lessons. I think it should be a mandatory part of education. Only through my travel I have learnt to adapt myself to any kind of situation. You become a sort of chameleon. You leave your routine and your daily life behind. Suddenly you don’t have these little daily routines or habits anymore. The sort of habits that used to affirm and comfort you. We easily create dependencies and habits, which become the conditions of our happiness, which makes it automatically tricker to reach this happiness. You’re always missing something.

The more I was moving, the less I was needing. I started in Los Angeles, an environment predestined to sell you all the stuff you supposedly need. Solutions come in form of vitamins, courses, self-help books, new fashion etc. There is a gadget for everything.

I packed my car with quite a lot of stuff that I ended up giving away as it didn’t serve me on my travel. That’s a beautiful realisation – we really don’t need much to live and survive. And in the end what you really need makes out who you are. We have to differentiate between the things that are pushed on us by society, and the things we need to follow our personal goals.

For me it’s my camera, paper and a pen. As soon as i get back into a city though, I’m dependent of my phone, my laptop, a connection to internet etc. As soon as you return to a more developed environment, you get automatically more needs. I think it holds you back from being happy and content. It gives you this constant feeling of needing something. We live in a society of collectors of goods, hobbies, friends, lovers …

The time you spend on the road by yourself teaches you to deal with your own thoughts. All of a sudden you become way more conscious about your own decisions and choices.

Speaking of society, solitude is another interesting point. The time you spend on the road by yourself teaches you to deal with your own thoughts. All of a sudden you become way more conscious about your own decisions and choices. Important is to stick with them. To believe in this decision you took as the best decision for you and your happiness. And accept everything that comes with it.

Artistically, the solitude and the unknown environment provide you with an immense aesthetic inspiration. Rather than being inspired by that same pool of visions, that people have in a city, you gain your inspiration from various impressions, visions and feelings that you don’t understand right away. I noticed how I was surrounding myself with people from the same field as when i was living in London and Paris. You automatically end up responding to the same moods, lightening etc. as everyone else. You end up constantly imitating each other in a way. Once you’re alone in an unknown environment, you start following a simple instinct, a little voice in your head, telling you what to do, without thinking too much about it. There was nothing or no one before you who did it that way. Of course this involves taking risks as well. The most valuable result of the risk you’ve taken is the satisfaction that you tried. You gain confidence from succeeding in something, from confronting your own fears.

In my photographic work, talking to strangers, almost intruding into their space and taking a very personal image, challenges me. The camera works like a safety shell and a weapon at the same time.

In my photographic work, talking to strangers, almost intruding into their space and taking a very personal image, challenges me. The camera works like a safety shell and a weapon at the same time. It defines your reason to be there and to do what you do. It’s like an excuse. An excuse that works for yourself, and sometimes for the people you’re taking photos of. I experienced this with the Mennonite community in Belize, as well as with the Romas in Rumania, or even in Cuba. Approaching people you have nothing in common with, sometimes not the same language, you share no experiences, you’re both unknown. It often starts with a feeling of aggression, intrusion. That’s the phenomenon of the “alien“ again – they can’t file you, they don’t know what to think of you. But even though you come from two complete different cultures, a friendly sign, a smile from your side already triggers a pleasant face and an open heart on the opposite side.

All images by Théo de Gueltzl. Text by Sophie Strobele.

Receive a postcard from us sign up