I put down the book and slumped back against the bug-ridden bed in my dingy roadside room halfway between Alice Springs and Darwin. “Exactly,” I sighed, a little too dramatically, then pulled out a pen and underlined the paragraph in Robyn Davidson’s ‘Tracks’: “I had sold this trip, misunderstood and mismanaged everything. I could not be with Aboriginal people without being a clumsy intruder. The journey had lost all meaning, lost all its magical inspiring quality, was an empty and foolish gesture. I wanted to give up. But to do what? Go back to Brisbane? If this, the hardest and most worthwhile thing I had ever attempted, was a miserable failure, then what on earth would succeed?” My three week excursion in Australia’s Northern Territory could hardly be compared to Robyn’s epic 1700 mile trek across the outback with her camels and dog Diggity but I could definitely relate.

I’d been working on a documentary photography project called Small Town Girl for three years. I used the internet to find teenage girls living in small towns across Australia, the USA and South Africa who’d let me stay with them and take photos of their daily lives. (It sounds super dodgy, I know, but it really isn’t – promise!) It had always gone so well and felt so right. I’d been welcomed into the worlds of teenage girls living in townships in South Africa, on farms in Texas, between mountains in Washington, and beachside at Byron Bay. Things generally fell into place at the last minute. Loose plans firmed up in the most unexpected and delightful ways. Random opportunities turned out to be far more enriching that anything I could have imagined. Time and time again these positive and thrilling experiences seemed to affirm the fact that this was what I was meant to be doing. So last November when I took a few weeks off work and booked a flight to Alice Springs to continue the project, I was quietly confident. I didn’t know exactly what to expect from Australia’s central desert and beyond but I knew it would be wonderful. I had the interest of a big media outlet and they were eager to see what I could come up with. I imagined meeting young Indigenous women and their families and learning more about their culture, then coming away with a deeper understanding and some stunning photos.

When someone else is sitting beside you in a four-wheel drive as you cry and complain about how you don’t have any pictures for Instagram it’s pretty confronting. I definitely exposed some ugly parts of myself that I’d much rather have denied or kept hidden.

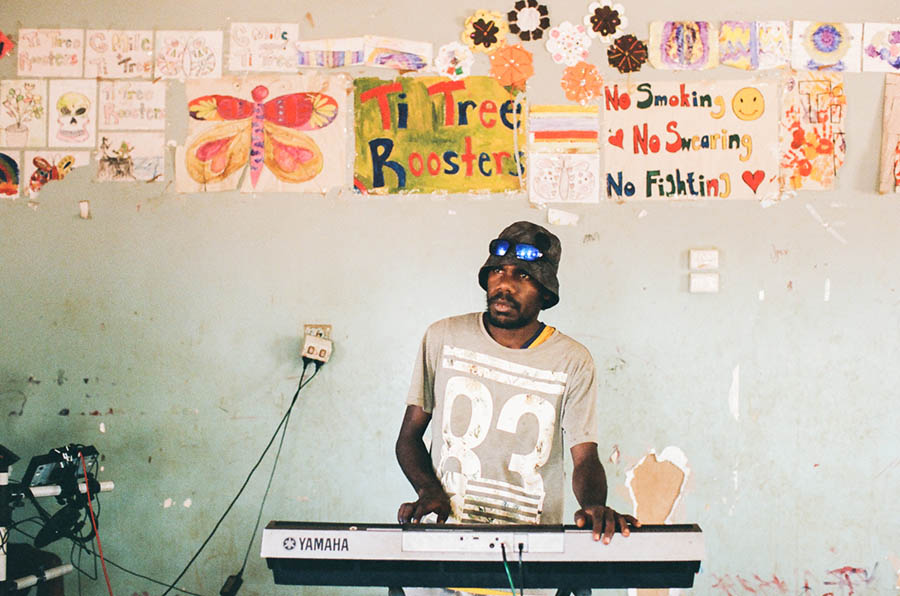

That’s not what happened. Plans fell through. People didn’t show up, or cancelled, or said yes but meant no. When I did get the chance to take photos during a music and song writing workshop I felt like I was in the way and stepping on toes. The white Australians who lived in the community were protective and acted as gate keepers – with good reason, I’m sure – but this led to feelings of misunderstanding and rejection. I questioned my intentions and second-guessed my motives.

Plus it was really hot – 40 degrees Celsius or more every day – and I was stressing out about all the money I’d spent to get there and the annual leave I was using up. I didn’t handle it well. My friend Simon, a TV camera operator and cinematographer, witnessed me at my worst as dark clouds gathered over my usually sunny disposition. When you face a trying situation on your own you have no choice but to step up and figure out a way over/around/through it then deal with the consequences. This is often made a little easier and less humiliating by the fact that no one is there to watch you melt down or fall apart.

When someone else is sitting beside you in a four-wheel drive as you cry and complain about how you don’t have any pictures for Instagram it’s pretty confronting. I definitely exposed some ugly parts of myself that I’d much rather have denied or kept hidden.

Somewhere along the road I started to see that while my original plans had fallen by the wayside some pretty awesome stuff was happening regardless. At a waterhole not far from Alice, we met a youth worker named Maria who invited us to her community a few hours north. She told us about a group of guys who’d put a band together and were trying to promote their music. Simon offered to record them playing live and I said I’d be happy to take publicity shots. We were welcomed into Pmara Jutunta community and immediately asked to join a team of local kids for a few games of twilight basketball. The next day Anmatjere Band set up in the community hall and played as we filmed three of their songs. Then we walked around the community as they posed for photos. Little kids followed along, in awe of their suddenly ‘famous’ dads, uncles, cousins and brothers in the band.

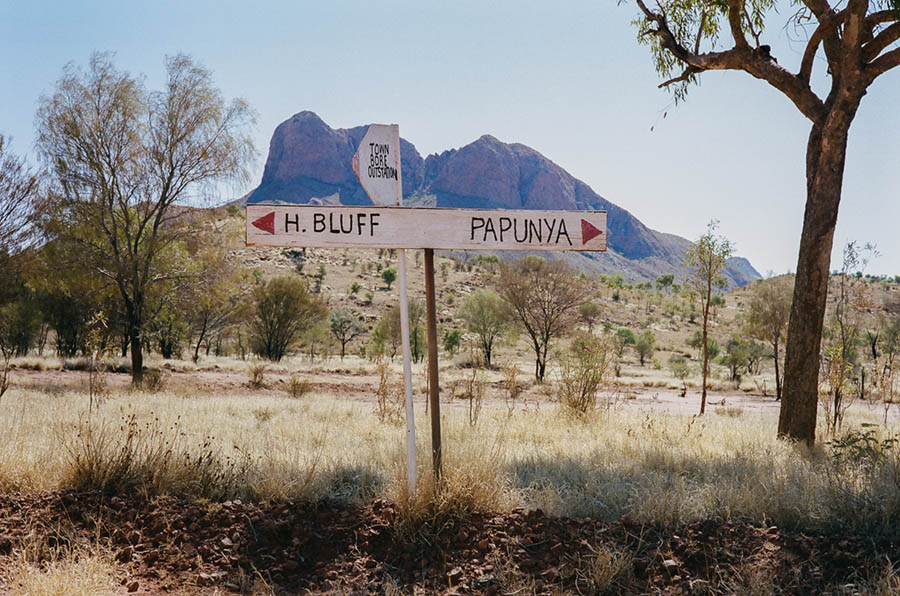

The ABC’s Double J radio planned to air a show on seminal 80s Indigenous group The Warumpi Band and asked me to travel to a community called Papunya and meet up with one of the original band members, an elder named Sammy Butcher. As Small Town Girl plans (and back up plans) had come to nothing, I had a fair bit of free time up my sleeve. The idea was to go and spend an afternoon with him, talk about his days in the band and take photos of the landscapes that inspired the group, the rooms they rehearsed in and the spots in which they shot video clips. When word came through that Sammy was indeed in town, we jumped in the four-wheel drive and flew across the dusty red dirt roads west of Alice Springs. But pinning Mr Butcher down was easier said than done. To fill in time we decided to check out Papunya Tjupi Arts. As we arrived at the centre, a group of ladies – all in their fifties, sixties, even seventies – filed through the door in front of us. Doris, Isobel, Nellie, Martha and more found their place on the floor or at a table, canvasses stretched out before them, cups of tea by their sides. They got straight to work and breaking their concentration wasn’t easy. Hunched over, they carefully marked their canvas with well-placed dots, swirling lines and swathes of colour. They appeared to work intuitively, with a natural sense of composition, line, space and tone. Watching them work was a pleasure and we ended up spending two days there, occasionally chatting about the art but mostly making toasted cheese sandwiches and re-filling their tea cups.

He talked openly about the struggle associated with living traditionally and acknowledging culture while trying to move forward in the modern world as well as the great divide between the Indigenous and non Indigenous way of life.

Spending time with Sammy was a real privilege and something I won’t soon forget. His warm welcome was such a relief and his wise words are with me still. He talked openly about the struggle associated with living traditionally and acknowledging culture while trying to move forward in the modern world as well as the great divide between the Indigenous and non Indigenous way of life. He explained the importance of the land and how it relates to identity and belonging. I discovered there was a song or a story about every tree, every waterhole, every rock formation. I saw the way family and community is valued above all else. The pieces of the puzzle started to fall into place, I began to understand.

I left the NT feeling confronted, challenged and unsettled. On one hand the trip felt like an “empty and foolish gesture” but on the other hand I knew that something important had been sparked in me, something that I would pursue and seek resolve.

I left the NT feeling confronted, challenged and unsettled. On one hand the trip felt like an “empty and foolish gesture” but on the other hand I knew that something important had been sparked in me, something that I would pursue and seek resolve. While I didn’t get back to Sydney with the stories and photos I thought I would, it’s hard to be mad about the unexpected experiences and opportunities I was presented with. I’m still wrestling with lessons I learned and trying to make sense of what I was told by Indigenous men and women along the road. It’s as if Australia’s “mythological crucible, the great never-never, that decrepit desert land of infinite blue air and limitless power” (Robyn Davidson again) has opened itself up to me in a whole new way and I’m here in the city, trying to figure out how to respond to this revelation.

Images and story by Elize Strydom

Elize Strydom is a documentary photographer and journalist based in Sydney. She travels to small towns across Australia, the USA and South Africa documenting the daily lives of teenage girls. She shoots film with a Canon 1V and a Leica M6 and you can see her work at @smalltowngirlproject, @twinrivers_ and elizestrydom.co

Receive a postcard from us sign up