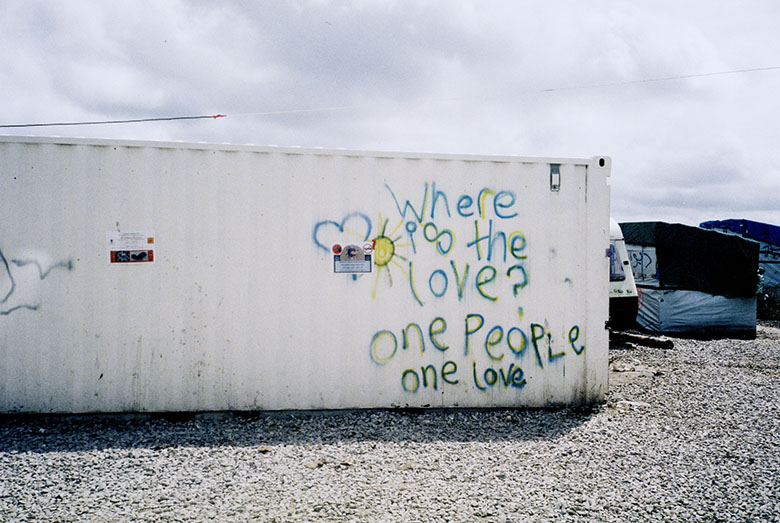

Watching the recent demolition of “the Jungle”, the notorious migrant camp on the outskirts of Calais, France, has brought many mixed emotions for us, as it did it during our time volunteering there in July.

Our decision to volunteer in Calais arose mainly as a means of aid and support to the people living in the Jungle, but also curiosity of what life there was really like on a day-to-day basis, and what issues the community faced for the future. We had already planned a trip to Europe when we found the NGO, “Care For Calais”, so decided that we would take a few weeks out to volunteer. We had been passionate refugee advocates for a long time, but always felt helpless, especially in regards to the situation in Europe. Both being documentary photographers, we hoped that recording our short time would help better people’s understanding of the importance surrounding the current government policies for refugees and asylum seekers, both within Australia and worldwide.

We were there to help hand out food, and help with visa applications and building shelters. Though important tasks, in reality it was sharing experiences over meals, or simply taking the time to be a friend and listen to people, that was more important. We soon noticed how much these people became like family, especially to our fellow long-term volunteers.

There is no doubt that the conditions in the camp under which people lived were terrible and worsening despite the best efforts of aid organisations on the ground. The state-sanctioned slum was previously rubbish dump, and migrants lived in wooden shelters, donated tents and under tarps through bitter and intolerable winters.

Ultimately the camp was made up of people trying to cross the English Channel to get to the United Kingdom, and for a lot of its residents, that goal still hasn’t changed. Keeping this in mind, the French government is perhaps a little naïve to think that migrants and refugees will stop coming to Calais, especially with no sign of the global refugee crisis improving. But life in the camp was tough and miserable, so to have the opportunity to be relocated to proper housing and given the opportunity for asylum and integration in France is a positive development.

Naturally we are still as worried about the people we met during our time in the camp as we were during our time there. One of the most difficult things about volunteering was the fact that at the end of the day, both you and the people in the camp know you’re eventually going to leave and go back to your normal life. And that’s one of the most difficult things – no matter how much you help, sympathise and empathise with somebody, you can’t trade places. You feel very helpless.

And that’s one of the most difficult things – no matter how much you help, sympathise and empathise with somebody, you can’t trade places. You feel very helpless.

It might sound strange, but we really enjoyed our time in Calais and found it very difficult to leave, despite the overwhelmingly sad circumstances of why we were there. We met amazing people from all over the world, including people living in the camp, and other volunteers. It might sound selfish, but there was something liberating about being there, with everyone equal, no matter the background or circumstances. We forgot about our dreams and ambition, common in our over-privileged lives.

It might sound selfish, but there was something liberating about being there, with everyone equal, no matter the background or circumstances. We forgot about our dreams and ambition, common in our over-privileged lives.

Our time in Calais cleared up many misconceptions. As terrible as the living conditions and daily malaise were, it was amazing to see how resilient the migrants were. They had created a town out of nothing – a main street with restaurants – and were always warm and hospitable. We thought there would be mostly Syrians living in the camp, but in reality they were the minority. Most people came from war-torn countries such as Afghanistan, Sudan and Eritrea; most had walked across Europe arriving with only the clothes on their backs, exhausted, distraught and terribly hungry. There were up to 100 new arrivals each day. Of the estimated 9000 people living in the camp, about 90 percent were young men, with around 800 children, half of whom were unaccompanied. It was surprising that nearly the entire camp’s population was made up of young men. The experience led us to a fundamental realisation that the people living in the camp were really no different to us. We ate, socialized, worked, and became friends with the people we met. They were doctors, professors and students.

One of the hardest things about our time in Calais was talking how Australia treats refugees, and our country’s offshore detention regime. Our opinion on Australia’s refugee policies didn’t change, but we felt a greater shame and embarrassment than ever before. It’s really hard to tell someone how nice a place Australia is, a country with supposedly the highest standard of living on earth, when we lock up innocent women and children in island jails who are just trying to escape war and poverty. It’s a sad day when you feel embarrassed to talk about the place you call home because it has the cruelest treatment of refugees on the planet. We hope in some small way our photos can open up further dialogue about treating refugees more humanely and create social and political change.

It’s a sad day when you feel embarrassed to talk about the place you call home because it has the cruelest treatment of refugees on the planet.

Text and photos by Michael Rees-Lightfoot and Jaz Blom. The pair have just released a zine, “Welcome to the Jungle”, which can viewed and purchased online here.

michaelreeslightfoot.com | jazblom.com

Receive a postcard from us sign up