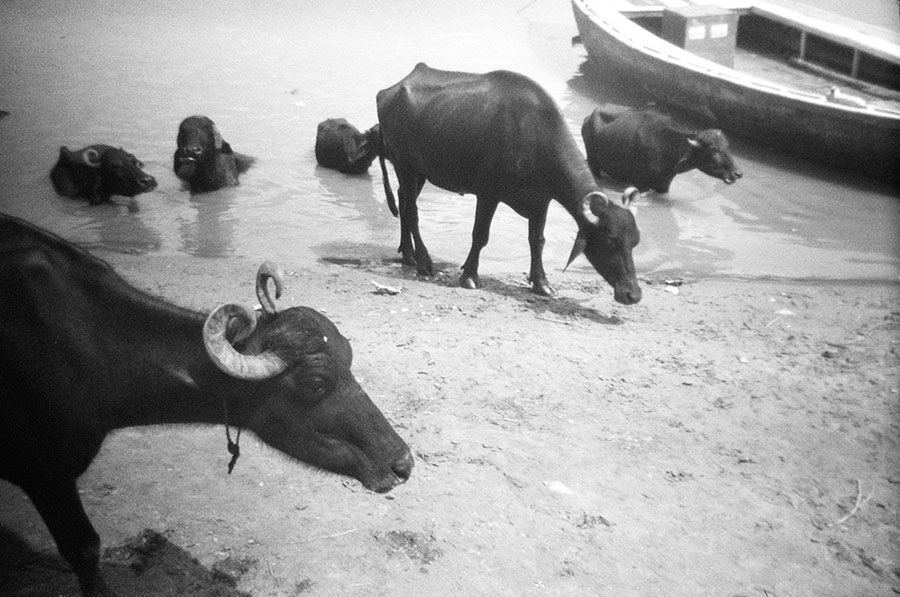

My Holga 135 was perfect for travelling through India. In comparison to other film cameras, the Holga has little to no settings. Its functions encourage a point-and-shoot approach, which sometimes results in happy accidents. Cultural interactions are assimilated the same way an image is exposed onto film. We’re provoked to press the shutter, to compress the memory to the size of our palms and remember it forever through evidence. We place everything we learned while travelling against the grain of our own cultures – a cross-process.

I was snap happy in India but it took me the better part of a year to get the film developed and realise what the images represented – India’s ability to transform a person. It changed me. I know it seems cliché but India is and always will be a place associated with finding oneself.

I was snap happy in India but it took me the better part of a year to get the film developed and realise what the images represented – India’s ability to transform a person. It changed me. I know it seems cliché but India is and always will be a place associated with finding oneself.

No friends had been before. An Indian man I was working with prior to departure suggested refunding our tickets. “But if you must go, don’t drink. They slip things in your drinks and then who knows,” he’d said. He was from Rajasthan and his lacking patriotism was a concern.

“We’ll be careful,” we reassured our mothers before leaving. Bad things happen everywhere.

My knowledge of India was based on Gregory David Robert’s Shantaram or Wes Anderson’s The Darjeeling Limited. Both portrayed a landscape where spiritual journeys take place in those willing to engage and accept that fate is wild. My other knowledge of India was disconcerting. My girlfriend and I were about to pack for a three-month trip around the sub-continent, with the decision unfortunately coinciding with the gang raping and subsequent death of a British tourist in Delhi and the hospitalisation of her boyfriend. Preconceptions were being shaped to that of mainstream media. India was a dark shadow we were chasing. “We’ll be careful,” we reassured our mothers before leaving. Bad things happen everywhere.

Sick in a Jeep

You pay somebody rupees for a shared Jeep up the mountain expecting shared means a few other people. I’m a red-faced Rubik’s cube contorting to thirteen other humans and one chicken. Knees meet my ears. Lower back spasms. The chicken is next to me in a hessian sack, its wild squawks silenced by the owner’s loafer. He slides a fifth of whisky from the inside pocket of his coat and waves it around as an offering. I move in my seat inching closer to comfort while Jess is pressed against the window trying to breathe. Something is coming on. I see it in her eyes.

I’m a red-faced Rubik’s cube contorting to thirteen other humans and one chicken.

We reach Darjeeling and find a place. They allow us to stay for one night only. The state of Ghorkaland, fighting for independence, stages regular strikes in which the hillside station of Darjeeling becomes ghostly. No one knows how long this strike will last. One night will do before the next Jeep ride. Jess has already collapsed onto the bed with malaria symptoms. I wander the streets in search of food. Every restaurant closed. A man sells me dinner in the form of apples and bananas wrapped in newspaper.

The ghosts of Darjeeling resurface. Town centre inundated with people waving rupees at drivers. We’re ushered to a Jeep and once again are placed in the back seat. “We leave soon,” the driver says despite the gridlock ahead of us.

Four hours later we’re on the potholed road again leaving Darjeeling. Nine hours later we arrive in Gangtok, Sikkim, another hillside station. The strikes never went ahead. Jess is face down on the mattress while I again set out in search of fruit. It’s late but I find a restaurant. Fruit salad’s on the menu. I pay, then head next door to a hole in the wall, but the waitress follows me to buy fruit for the fruit salad. She buys pumpkin then hands me a plastic bag of pumpkin and yoghurt.

It must be 2:30am and I have three seconds to get to a toilet. It’s finally happened. I’m glad I have a Western toilet in our room. Someone did tell me that no matter what you do, you will get sick in India. It’s more or less an adjustment to the abundance of red chilli powder.

Kilos are lost over the course of days. Jess overcomes her malaria scare and joins me by the toilet. Any chance of sightseeing or adventure is thwarted by the need to have a toilet within reach. Even walking out into the street for breakfast results in hunched over agony, unable to continue, about to burst.

We take turns. We buy more toilet paper. We listen to hours of music through noise-cancelling headphones, a fumbling panic to put them on before the other goes about their business.

Sick on a bus

We flag the bus down. It nearly left without us. We throw our rucksacks beneath and climb aboard, taking our designated seats in the last row. Two middle-aged women turn in their seats to watch us. Half an hour later they’re still watching.

The sun setting somewhere over Jaipur tells everyone to leave their seats and enter their horizontal berths above. I do so gladly, excited by the prospect of sleep and glad to remove the women’s eyes. Unfortunately the back of the bus also means copping the brunt of any potholes, which is likely on a sixteen-hour journey from Pushkar to Rishikesh. I underestimate the extent and depth of them. This bus has no suspension. Each time a wheel enters the earth I’m sent flying. A thick plume of dust releases from the thin mattress when I land. Poor Jess and her small frame go with every corrugation. I’m there to catch her elbows in my ribs. Somehow we fall asleep.

The bus stops every few hours for toilet breaks. Women wait in line at holes in the ground or simply hike up their saris in the field. Men stand like incense in sand, pissing in the wind. I get up to stretch my legs. I don’t feel so good.

Women wait in line at holes in the ground or simply hike up their saris in the field. Men stand like incense in sand, pissing in the wind.

It’s somewhere near midnight and we’re back on the trampoline in and out of gravity. Our slow progression toward the yoga capital continues. I drift into sleep but can’t sustain it, waking to the feeling of waste moving through my intestines. I’m exhausted. I’ve never been so afraid to close my eyes.

I spend the wolf hours waking to clenched butt cheeks and suppressed childhood memories.

These are only two of the more embarrassing memories from India. Much like developing film, happiness takes time. Through India I saw different shades of frustration, anger and sadness, now filtered through a lens of laughter. It’s those unhappy moments that are remembered for what they become.

Through India I saw different shades of frustration, anger and sadness, now filtered through a lens of laughter.

No one warned us these things would happen. I may have brought a spare change of underwear if they had, but would’ve ultimately let destiny run its course. Unfortunately destiny also meant the death of my grandfather and cancer diagnosis of Jess’s father. We were ordered not to come home despite our best efforts. But looking back, we were exactly where we needed to be. India was embracing us, teaching us a little more about ourselves which enabled us to better handle our tragedies. Perhaps our parents knew this was the case.

Travelling through India belongs to the individual – moments and memories forged between country and self. There were of course happier times, life changing even. But I wrote about the embarrassing ones to warn about some of the fine print and inspire people to travel India and live a little closer to the earth. I’m concerned with First World problems as I write this. My laptop has distressingly little charge and Jess’s Himalayan salt lamp is increasing our power bill, somewhat. Life is far less complicated with a rucksack and minimal possessions. Life is far more thrilling chasing shadows through India. You’ll never know what lies between the borders unless you let the light in. It far outweighs the darkness.

Words and images by Aaron Chapman

Receive a postcard from us sign up