I’d packed the night before; some clothes, a few tools, a camera, and a laptop, all stuffed inside two waterproof bags, and strapped to the tail of my motorcycle. It was a mid-90s, large-capacity Honda, and with two years’ work, it was more mongrel than original – fast, homemade, and familiar.

As I readied to leave my kitchen, thick clouds ensconced a rising sun, and backyard shapes seeped into solidity under a grey veil of drizzle. There were 700 miles of Texas highway to ride, through downtown Houston traffic, along the deserts of the Mexican border, over the mountains of Big Bend, to the town of Alpine, and the route of the Trans-Pecos Pipeline (The TPP).

12 miles west of Presidio, the site of the Mission San Francisco, built and maintained since 1683. The Trans-Pecos Pipeline will pass through this site as it crosses from Texas into Chihuahua, Mexico.

The TPP is a natural gas transmission project that will snake its way across 143 miles of ecologically and protected Texas ranchland, and a further 456 miles of Northern Mexican countryside, eating through forcibly claimed private land as it’s built. The pipeline is 42 inches in diameter and will carry as much as 1.4 billion cubic feet of natural gas a day, under 1,400 pounds of pressure per square inch. Protests from locals on both sides of the border are regular, loud, but unheeded.

“In Northern Mexico, towns are abandoned,” says Tony Payan, Director of the Mexico Center, at the Baker Institute, Rice University. “You can’t tell by the land, but you can tell by the houses. Some of them even bear the signs of shootings. You can see the bullet holes in the walls.”

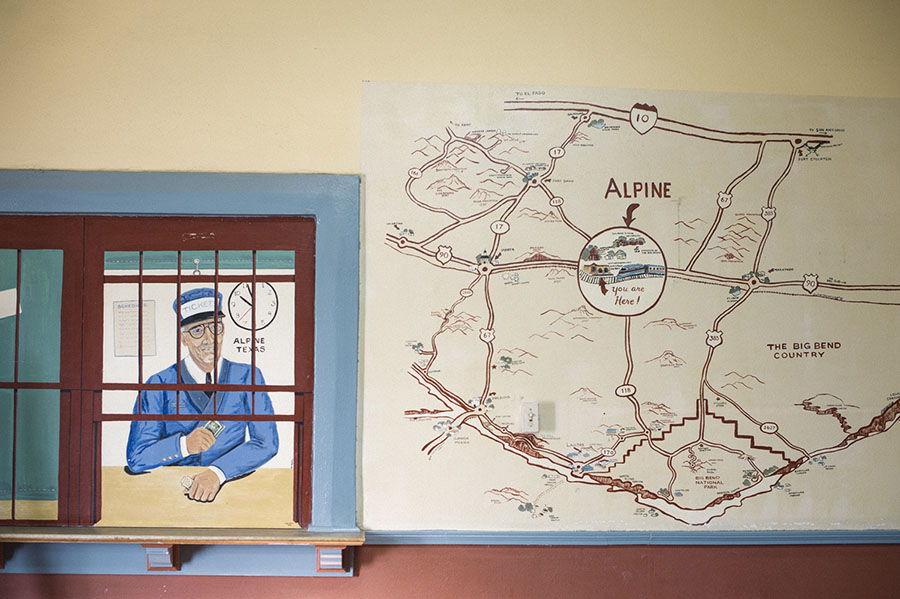

Alpine’s disused rail line has been temporarily strengthened to allow Energy Transfer Partners to transport pipe along its length, delivering to holding yards along the pipeline’s proposed route that runs parallel. Locals worry that increased industrial infrastructure through the pristine Big Bend area will leave the way open for the transportation of fracking chemicals and hardware into a previously unaccessible area.

Since 2011, my work as a journalist has pulled me overseas, away from my native England, and my transplanted home of Texas. Return trips have been to recuperate, and reconnect, but never to document. With a grant from the Society of Environmental Journalists, I was excited to make a contribution to the place that I live; to meet its people, and offer a voice to my community. Through late 2015 and early 2016 I began making motorcycle trips to West Texas to document the pipeline’s route.

Riding down the small main street of Alpine, dead center of the Trans-Pecos Pipeline route, past the cinema, Chinese takeout, two coffee shops and a hotel, the town’s residents were protesting.

Riding down the small main street of Alpine, dead center of the Trans-Pecos Pipeline route, past the cinema, Chinese takeout, two coffee shops and a hotel, the town’s residents were protesting. Scores of people flapped “No Pipeline” flags at traffic, and appealed for waves from sympathizers. In communities like Alpine, anti-pipeline campaign groups like the Big Bend Conservation Alliance (BBCA), and Defend Big Bend, have grown in popularity. Support has snowballed through the United States with thousands of social media followers, dedicated concerts and events in Austin, Texas, and fundraising in New York.

Terry Bishop and his wolf in Presidio. Bishop campaigns against the Trans-Pecos Pipeline. He is an active environmentalist, instrumental in creating the BJ Bishop Wetland on the Texas, Mexico border. The conservation effort supports wildlife habitats that have been impacted by water shortages due to industry and agriculture.

The church at Shafter, Texas. Shafter was the home to at least six silver mines in the 1900s. Sitting between Marfa and Presidio, it’s exactly on the Trans-Pecos Pipeline’s proposed route, and is home to just 30 people. In 1971 was the set for several scenes in the movie Andromeda Strain.

In the midst of the protest I met Mattie Matthaei, Executive Director of the BBCA. Wrapped in a green corduroy jacket, she was energetic and offered immediate shelter – some manual labor in return for sanctuary in a trailer parked behind her historic, mid renovation hotel. Inside, the trailer was bare wood paneling, or painted dark green. There was a small sink, a landscape oil painting, and a heater to stave off the freezing nights. I tied a hose to the fence, to use as a shower, and settled into work.

Alpine and the route of the Trans-Pecos Pipeline fall inside the Chihuahua Desert, one of the three most bio-diverse desert regions on Earth, and home to the Big Bend State Park, McDonald Observatory, the Marfa Lights, 446 species of birds, 3,600 species of insects, over 1,500 plants, and 75 species of mammals. Conservationists are concerned about the destruction of nearly 1000 acres of Priority Conservation Area by the TPP, and the disturbance of 45 high-risk Conservation Target Species.

In 2010 President Obama and then-Mexican President Calderón recognized the ecological value of preserving the Chihuahua Desert in the cosigning of a Bi-National Agreement.

“This is an area that’s been relatively free from industrial development. It gives this country a different feel from other places in Texas,” said Joel Nelson, a veteran of the Vietnam War, celebrated poet, and professional cowboy. “It feels good to me. That good feeling is not going to remain if we start making impacts on it.”

As we talked, Joel eased his Ford F-250 truck over the dried-out tire ruts in the earth. His wife, Sylvia, was in the back with an open bag of cattle feed. A herd of brown and black Corriente cows crowded around, chasing the procession as Sylvia threw handfuls of feed out of the open tailgate. They stopped the truck pointing south-east over countless miles of dry dirt and bristly mesquite to show the proposed route of the pipeline, straight across their 24,000 acre ranch.

Alpine, Texas, seen from Hancock Hill. The Trans-Pecos Pipeline will brush the suburbs to the west of the town, across the plain below the mountains, passing through private ranch land adjacent to the hospital and the airport.

Energy Transfer Partners, responsible for the TPP build, made the Nelsons an offer for the land that the pipeline would bisect. “For every $5.46 they’d own 1ft by 50ft of permanent easement. Which comes out to a little under $30,000 per mile. Forever,” said Joel as he climbed out of his truck’s cab, sinking worn, grey cowboy boots into sand on his way to count cattle. The offer was a long way below market value.

“There’s probably an amount that we’ll be forced to settle for; if we don’t make some sort of agreement with them they’ll condemn our land. It’s a bitter pill to swallow.”

Joel Nelson drives past a pipe storage yard on ranch land adjacent to his. His private road is shared by five land owners. As long as one landowner grants Energy Transfer Partners permission to use the road, the construction company is legally permitted. Nelson worries that 18-wheeler traffic will leave the road requiring repair.

The Texas portion of the TPP project alone is worth nearly $770 million in private contracts, and claims to operate under a Certificate of Public Convenience, as a benefit to local economy and public gain, allowing its politicians to grab private land by eminent domain.

Opposing locals in Texas resent the imposition of industry into one of the few untouched areas of the state, and worry that it could open doors for expansion, pollution, and development. In one of the last truly natural escapes in Texas, they fear falling property prices, trespassing surveyors, and the seizure of land by bureaucratic force.

42 inch gas pipe stacked at Energy Transfer Partners’ storage yard in Fort Stockton, Texas. Through early 2016, pipe from this yard at the beginning of the route, is loaded onto flatbed railway cars and hauled down a disused railway line, to be unloaded into other storage yards along the route of the pipeline.

Five miles south of the Nelson’s ranch in Alpine, I visited Suzanne Bailey for tea. When I arrived she was stood in the 2-meter gap between her tiny yellow bungalow and its property line, photographing the progression of a 24-acre facility directly next door. The land was bought in the summer of 2015 by Pump Co. – who are also contracted to build the TPP – and is intended as an engineering yard for specialized lengths of pipe, a quarter mile from the pipeline’s route.

“I’ve had to get in my car and leave. I deeply resent having to leave my house. I deeply resent being forced.”

“They’ve changed the topography to the point that it floods our property. We’ve flooded three times in the last few months.” Suzanne, a petite lady of around seventy years old, is dressed in slacks and a pink and green plaid shirt. “I’ve had to get in my car and leave. I deeply resent having to leave my house. I deeply resent being forced.”

Joel and Sylvia Nelson, round up their cattle for vaccination.

Joel Nelson helps his wife Sylvia over one of their fences while out feeding and counting cattle. Energy Transfer Partners are planning to cross the Nelson’s 24,000 acre ranch with the pipeline, and threatening eminent domain to seize the Nelson’s land by force. “For every $5.46 they’d own 1ft by 50ft of permanent easement. Which comes out to a little under $30,000 per mile. For ever,” says Joel. The offer is a long way below market value.

For the first four months, Pump Co. worked eleven hours a days beginning at 7am, clearing, raking and compacting the earth. “They had pieces of equipment that are called vibratory soil compactors,” says Bailey, “I really thought the house was going to fall down. It was like going through an earthquake.”

There are some who welcome the pipeline: Texan landowners who would relish royalty checks paid for ranch access, and some in the border town of Presidio who welcome the possible rise in manual employment around the line’s construction, however hollow that hope may be.

Suzanne Bailey, in her home on the outskirts of Alpine. In the summer of 2015 Pump Co., a contractor of Energy Transfer Partners in charge of pipeline construction, bought a 24-acre plot of land near to her house, to store machines and refueling equipment. “They’ve changed the topography to the point that it floods our property, we’ve flooded three times in the last few months,” says Suzanne, “I’ve had to get in my car and leave. I deeply resent having to leave my house. I deeply resent being forced.”

Sarah Martinez, employment agent for Workforce Solutions in Presidio, Texas. Many residents of Presidio, where the Trans-Pecos Pipeline will cross into Mexico, are in favor of the project. They hope that construction will bring employment to the area. “We’ve got around 150 men on the books waiting for work. We have the lowest employment rate in the region, somewhere around 8.27%,” says Martinez.

Jesus Carrasco has moved to Presidio from Lovington, New Mexico. With a slump in oil prices he lost his job as a salesman for an energy company. Now he earns $10 per hour working for Shopco, a chain furniture store on the edge of town. “I’m waiting for a job on the pipeline,” he says, “in the energy industry I earned $8,000 every two or three weeks.”

Between January and March of 2016, disused rail lines along the Texas portion of the project were alive with freight cars hauling three monstrous pipes each. Heavy machinery with suction grabbers waited alongside trains, ready to stack the pipe in storage yards. In Mexico, compensation was being denied to families forced from land, and pressure was applied to local press to stay close-lipped.

Sat on my Honda, shivering under layers of armor, fleece, and leather, I banked through the turns of the West Texas hills, exploring the route – Fort Stockton, Marfa, Shafter, Presidio, Ojinaga, Alpine. With my chest on the fuel tank, elbows tucked in, I guided the bike with incremental shifts of weight. Frigid gusts of wind would tug as they passed, straining head, arms, and neck, like North Sea waves against neoprene wetsuit. The noise was a roar of wind, the engine whine lost to white noise tinnitus. The ochre scenery blurred past, and I was lost in thought.

Ana Luján Marín, a teacher from Chihuahua City, involved in campaigning against fracking and pipeline development in Northern Mexico. “The Trans-Pecos Pipeline will create the illusion of employment,” she says, but is certain that it won’t benefit local populations.

Osvaldo Moya, a lawyer from Chihuahua City, Mexico, campaigns to stop the Trans-Pecos Pipeline. Land in Chihuahua “has been taken in a violent manner, in a psychological way. If you don’t sell maybe you don’t get paid anything,” he says.

I felt sad for the Big Bend inhabitants, for the residents of Chihuahua, the idea of American freedom, and our crumbling concepts of democracy. Despite White House petitions, regular public protests, detailed scientific reports about the ecological fragility of the area, and appeals to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, it seemed the Trans-Pecos Pipeline and its Mexican twin would grind onwards toward inevitable completion.

@spike_johnson

Spike photographs in the documentary style, exploring themes around environmentalism, religious friction, and self sufficiency, focusing on rural areas of Myanmar, the United States, Central America, and England.

Receive a postcard from us sign up