‘Our days are a kaleidoscope. Every instant a change takes place in the contents. New harmonies, new contrasts, new combinations of every sort… The most familiar people stand each moment in some new relation to each other, to their work, to surrounding objects.’ – Harry Ward Beecher.

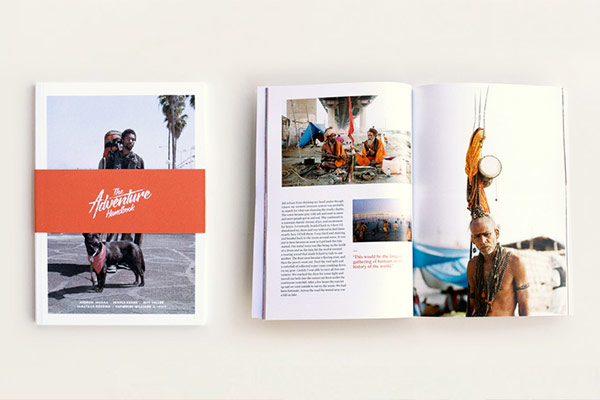

I arrive on the eve of Diwali, as candles flicker silently from the cusp of each street corner and saris swish elegantly on the banks of the Pushkar Lake, known in Sanskrit as ‘Ketaksha’ or ‘raining eyes’. Unlike the lavish, loud celebrations that happen elsewhere in the world on this night, in the holy city of Pushkar nestled in the deserts of Rajasthan, it is a quiet affair, as locals pay respect to their gods and then retreat home to their families.

I came to Pushkar for a camel fair – one of the world’s biggest, most famous and well-visited – but arriving almost two weeks before the official events began meant I got the opportunity to fill my time with new faces and experiences. Pushkar is full of life, and all walks of it. The whitewashed streets of the old city jam falafel stands with groups of Israeli travellers, Tibetan garden restaurants, Hindu pilgrimage temples, and colourful groups of gypsy tribes side by side. It’s a kaleidoscope of everything I have come to love about India: that fruitful, unforgiving land which has held me and carried me so tight through my months of solo travel there.

It’s a kaleidoscope of everything I have come to love about India: that fruitful, unforgiving land which has held me and carried me so tight through my months of solo travel there.

I meet Ram at the beginning of the trip; a street musician who spends more time drinking chai with backpackers than playing music on any streets. Instantly he tells me about his friend, Aloo Baba, a holy man who lives out in the mountains around Pushkar and survives off only potatoes.

The next day we drive over sandy terrain and through villages to Aloo Baba’s home, a concrete structure built by members of the community. He’s one of the friendliest Babas I’ve met, open to my visit and me photographing him between puffs of hashish. The grounds of his home are green and lush, a great contrast to the desert dunes around. He has planted over 300 trees with the help of the community, and for some unknown reason, around 50 wild peacocks have slowly gravitated towards him to live among the trees. When no one else is around they will come right up to him, he tells me with a proud aura. We leave just as his morning brew of potatoes is ready, a meal he supplements only with lashings of chai and hashish throughout the day. He reads the newspaper in Hindi and awaits his next visitor.

Ram talks incessantly about his wife, and encourages me to come back to his village to meet her. The village is spread across a flat dune, where goats and dogs run rampage through the garbage that unfortunately covers the ground between homes. He dips his head under the doorway and we sit on a wooden bed frame beneath twigs intricately twined to keep the light out, but he tells me that in the monsoon, the roof cannot withstand the heavy rains that shatter the villages around Pushkar.

Their baby girl is bright-eyed and as beautiful as her mother. ‘She’s such a happy baby, we are very blessed,’ Ram tells me, ‘but she wants milk all the time, too much!’

Ram’s wife is tall and slim with a long nose and beautifully unusual bone structure. She wears a ragged pink sari and an assortment of fake silver jewels that seem to be crumbling under the weight of the work she does everyday. She’s shy and only a year older than me, grasping her baby under one arm as she pours chapati flour onto the floor and begins kneading the dough. Their baby girl is bright-eyed and as beautiful as her mother. ‘She’s such a happy baby, we are very blessed,’ Ram tells me, ‘but she wants milk all the time, too much!’

I never catch the long name of his wife, but she cooks up a feast of chapatis and okra curry for us, followed by a pot of sweet, spicy chai. They give me everything they can, a trend I have found across the developing world. The camel fair is coming, and I notice the dunes on our way back to Pushkar are already dotted with herds of the beasts alongside their owners. It’s Ram’s least favourite time of the year, but in that afternoon sun, with the backdrop of mountains, I cannot yet see why.

A few days later I find myself among the camel herders as dawn pierces the horizon line. More chai is on the menu, and as I watch the day begin, the camels are fed and reared and the children of the herding families run barefoot through the dune sands, ravished by their new temporary home. Most come from the deserts around Pushkar and wider Rajasthan; some are nomadic gypsy families, while others move only for the camel fair then return to their village. The aim for these families is to sell a few camels for a good fee, and perhaps pick up a few more. I am told that the sale of one camel can result in enough money to feed a family for six months.

The aim for these families is to sell a few camels for a good fee, and perhaps pick up a few more. I am told that the sale of one camel can result in enough money to feed a family for six months.

A young girl collecting dung for fuel in the dunes

A camel herder in the early morning

Women in Rajasthani dress float through the wind on the grounds of the Pushkar fair

The fair attracts thousands of camel herders each year, and now also attracts tourists from all over the world. It’s obvious to me why so many people come here – that magnetic pull of colour; the livestock and unusual faces wrapped in bright yellow turbans are all unique sights for most foreign eyes. But for the herders who grace these dunes each year, the increase in white and East Asian faces is clearly confusing and damaging for the original spirit of the occasion, and camel trading seems to have taken a backseat as tourist dollars are far easier to acquire.

But for the herders who grace these dunes each year, the increase in white and East Asian faces is clearly confusing and damaging for the original spirit of the occasion, and camel trading seems to have taken a backseat as tourist dollars are far easier to acquire.

A camel herder at Pushkar Camel Fair

A herder and his camels in the early morning

Portrait of a young camel herder

When the official proceedings kick off, the narrow streets of holy Pushkar become congested and chaotic. No longer is this the quiet, hippie town it was a few weeks before, as prices triple and most of the lakeside hotels are taken over by tour groups. I stay for the grand cultural events – watching young girls swirl in traditional Rajasthani clothing, the infamous moustache competition, and the prize camels parading in jewels greater than their own weight. It’s a spectacle but it all feels a little too separated from the dusty-footed, turbaned men sat around fires smoking bidi, overlooking their camels.

Girls in traditional Rajasthani dress at a cultural event of the Pushkar Fair

Portrait of a girl in Rajasthani dress at the Pushkar Fair

I retreat to nearby cities, and return days later when things are returning to normal. It doesn’t take me long to find Ram, in his usual corner of the bazaar’s most authentic chai shop, chatting to a group of bearded men in mala beads and elephant pants. I gift him a book of prints I shot at his home and around the city of Pushkar – they include intimate shots of him and his baby, the first photographs he has of her. As he looks through at my depiction of his life, tears appear in the corners of his eyes, and he thanks me profoundly for this small gift. He tells me of his dreams for his daughter, and how far he feels from the lives of the travellers with whom he spends each day talking. I feel overwhelming gratitude for the simplicity and happiness he has shown me.

He tells me of his dreams for his daughter, and how far he feels from the lives of the travellers with whom he spends each day talking.

Pushkar returns to her usual self, holy and calm, spirited and still. The camels return back to the deserts, and the plains sit empty; the Ferris wheels come down, the glitter and glitz of the fairground silenced for another year. But the real beauty of Pushkar becomes more and more apparent in the days after the celebration, as Aloo Baba continues to eat his potatoes, and the locals chant prayers down by the holy lake. Out of the haze of festivity returns the kaleidoscope of India: the contrasts and the chaos; the simple, spiritual Pushkar I love the most.

The camels return back to the deserts, and the plains sit empty; the Ferris wheels come down, the glitter and glitz of the fairground silenced for another year.

Ram holds his baby daughter in their village hut outside Pushkar

Sun sets over the camel dunes in Pushkar

Story and images by Annapurna Mellor

Receive a postcard from us sign up