Hoda Afshar was born in Tehran, Iran. Completing a Bachelor’s degree in Fine Art (Photography) in Tehran, she began her career as a documentary photographer in 2005. Now based in Melbourne, Hoda practices as a visual artist, and is currently a PhD candidate in the Department of Art at Curtin University, as well as a lecturer at Photography Studies College in Melbourne. In 2006, Hoda was selected by World Press Photo as one of the top ten young documentary photographers in Iran to attend their Educational Training Program, and in 2015, she was selected as the winner of National Photographic Portrait Prize. She has been exhibiting locally since 2007 and also internationally in major photography festivals such as Pingyao International Festival of Photography in China (2012) and PhotoVisa Festival of Photography in Russia (2013).

Hoda summates her ideas in her preface of the series: “my country of birth, and a country that’s often either misrepresented, or simply misunderstood…”

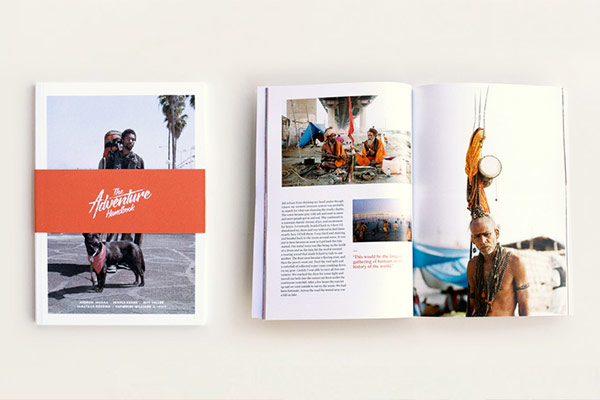

Hoda has spent the last few years exploring her own changing relationship with her motherland in an ongoing series of work, “In the exodus, I love you more”, which documents the changing face of Iran. Hoda summates her ideas in her preface of the series: “my country of birth, and a country that’s often either misrepresented, or simply misunderstood, whether because of ignorance, or because of the difficulty in navigating the surface in a place where the surface and depth often exchange looks … It is a record of my own evolving vision of my homeland – an insider vision that’s been shaped by the feeling of distance that accompanies migration – and a documentary exploration of the interplay of presence and absence and the truth that emerges in between”.

Ahead of the first exhibition of the series in November, The Adventure Handbook is excited to share a selection of Hoda’s recent images from “In the exodus, I love you more”.

Through my practice, I reflect on issues related to power relations, representation, displacement and identity politics. My artwork attempts to open lines of communication in a world both homogenized by global economy and unsettled by mass migration. I test diaspora, exoticism and cosmopolitanism for artistic and uncanny image-making possibilities.

I left Iran nearly a decade ago. I left and moved to Australia—to the end of the earth—leaving much behind.

I left Iran nearly a decade ago. I left and moved to Australia—to the end of the earth—leaving much behind. And like all migrants, I miss the things I left behind: the taste of the air; the trees’ sweet smell; the song of the streets and of the crows at sunset; the show that the sunset puts on in summer against the backdrop of the grey polluted sky; the tall mountains that hang like a curtain behind the city’s outline. My memory clings to these things, and somehow, my distance increases their nearness to me—these things that are always for me both there and not.

Most of all though, I miss my family. We speak every other day—across lines that make them seem both here and there. But even when the lines go silent I am somehow still speaking to them and they speak to me. And I wait till next I will return. Since four years ago, returning home has not been the same. I lost my father, and now the feeling that he is missing fills everything. It is not like missing other things whose absence refuses your desire that they appear. When I return to Iran, my father’s not being there is everywhere.

Eight years after my migration—right after my father died—I decided to make work in Iran again, where my passion for photography and storytelling had begun. I stopped making work there after my migration because the distance made me feel unauthorized to. Every time I return, I notice how things have moved on. As they do. Or as some things do. But anyway, that is what migration does to you: you tend to notice too much what has changed and what has stayed the same because of the way your memories cling to things. It colors everything.

I decided to make work about my changing relationship to Iran and about the Iran that I can only see through my father’s eyes. He taught me everything about my home: about its poetry and its history and landscape. He seemed connected to that earth, and for me he still is. The way he would tend to his garden: I knew he knew the language that that earth spoke. They lived in conversation. I knew it because one day, when my father went away, those plants stopped growing. Literally. They did not grow. Even when we tried to talk to them.

I decided to make work about my changing relationship to Iran and about the Iran that I can only see through my father’s eyes.

I wanted to make work about these things: about his Iran through my lens and my Iran through his. But it is hard to make work about what is not there, or there in a way that is inseparable from your having been away. To make others see what only you can see.

I simply began taking photographs. Without a clear destination. Without any expectation. I began making exactly the kind of work I tell my students not to make. I took photographs and I waited for the idea to appear. While waiting, I noticed that everyone and everything in Iran also seems to be waiting for something. Waiting with hopes and expectations. Waiting for something to change or for a sign that things are changing even as everything is changing. Expecting that we will recognize that something-we-want-to-arrive when it does arrive. At last. But feeling that there is always something missing in what the future brings.

What I realized through these experiences is that things can be missing in different ways—that absence clothes itself in different forms of presence. Realizing this, I stopped looking for that lost object of my desire.

My approach in making this series, then, has been to invert these feelings of expectation—not to expect but to let the surface speak; to embrace suspense and distance and turn them into a kind of seeing; to let what is both there and not there shine through the surface; to see reality as suspended.

In Iranian art, the surface and the depth combine in the play of presence and absence. It is a visual language that I have unconsciously developed. The language of the surface.

I believe Iranian artists have mastered such a way of seeing and configuring surfaces—a way of seeing the surface and the depth of things, the past and the present, inside and outside, simultaneously. Look at our Persian miniatures. The way that different spatial directions and non-simultaneous times are all there folded out on a single plane. In Iranian art, the surface and the depth combine in the play of presence and absence. It is a visual language that I have unconsciously developed. The language of the surface.

Making images is about seeing the surface. But the way the surface speaks, too, reflects the language that we carry within us—the stories that you share with a place. Images, I believe, are dialogues. Photography is storytelling. And so, about taking images of my homeland, it is not about having the authority to speak. I do not want to author its history. Photographing a place is about patiently learning the language of a place and its history. It is about learning to read and to see. Or better, it is about learning to converse, and through conversing discovering what you share, and sharing what you’ve seen.

@hodaafshar | www.hodaafsharart.com

Receive a postcard from us sign up