As I boarded the Air Koryo flight I grabbed a copy of the Pyongyang times before finding my seat. I read the headline article about Kim Jong Il’s undying love for his country and the Korean people. A second article detailed how the South Korean puppet regime and the United States had been caught plotting to blow up a statue. I settled in and thought about my journey ahead. I was still somewhat shocked that I was able to travel to the DPRK. A few years ago I had watched a documentary on the country that had sparked my interest in visiting. After spending a few months in China near the Korean border, I decided it would be an opportune time to visit the hermit kingdom. I contacted a travel agency, and after a few weeks of communication, had booked a tour to North Korea.

Propaganda played on the in-flight entertainment system, operatic tunes accompanied melodramatic war scenes.

Propaganda played on the in-flight entertainment system, operatic tunes accompanied melodramatic war scenes. Otherwise the flight was fairly mundane, drink and snack service, cramped seats. Descending into Pyongyang, I caught sight of soviet era military equipment aligned on the tarmac. Olive green cargo planes, helicopters and jets. Each vehicle had DPRK flag painted on the fuselage. I began to second guess my decision; thoughts of being detained crept into my head. It was too late to get cold feet.

I met my guides, Mr. Lee and Ms. Won. My cellphone was confiscated at the airport, my bags were x-rayed. Oddly enough, they didn’t look at my camera equipment. Outside, we met my driver, Mr. Oh. He was significantly more tanned than my guides, and he didn’t speak English. We drove for a half hour to my hotel as Mr. Lee explained a bit of the itinerary. I stared intently out the window, somewhat dumbfounded that I made it to North Korea. There is so much attention on the country from the Western media, it is treated as bizarre and walled away. I was rather perplexed that it had been so easy. I was expecting high levels of scrutiny, denied Visas, interrogation – none of which materialized. In fact, it was one of the simpler entry processes I’ve experienced arriving in a new country.

We drove towards Pyongyang. Green fields gave way to austere apartment blocks. Many looked unfinished, large concrete shells with minimal adornment. Some were painted a pastel green, yellow or pink. Most were cement gray.

Military men in their olive green uniforms marched and milled about. Civilians wore plain colored clothes, muted blues, grays and browns. The highway that ferried us into the city was giant, large enough to fit eight lanes of traffic. Save for a few other tourist vehicles or military trucks, the expanse of asphalt was empty. The road was in terrible shape; pot holes every few hundred feet. Though the road was empty and vast, we had to drive slowly to avoid damaging the car.

Save for a few other tourist vehicles or military trucks, the expanse of asphalt was empty.

As we entered more populated districts, I saw trams and old buses packed with people. We passed unique looking buildings. Sporadically, I’d catch a glimpse of a propaganda monument or poster. Giant Korean text in a red font spanning the tops of buildings, pictures of Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il looking benevolently in to the distance.

The city was silent save for a few bicycle bells, maybe a bus engine coughed in the distance. Very little activity was occurring in the street. No noisy mechanical systems, no snarling dump trucks or jackhammers, no hucksters or buskers, no advertisements, no goods being hocked. Just unadorned walls, every now and again a white sign with blue letters, indicating what is sold from the business within.

My hotel was on an island and under the terms of my tour I was not to leave the property by myself.

My hotel was on an island and under the terms of my tour I was not to leave the property by myself. We pulled up and were greeted by white gloved bellmen. I was escorted to an elevator that bounced as people and bags were loaded inside. We shot up to the 37th floor and the doors opened briefly. They started shutting on me as I was still in the threshold. No safety mechanisms here. The hall smelled of stale cigarette smoke, more muted and flat colors.

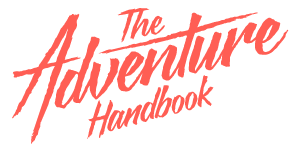

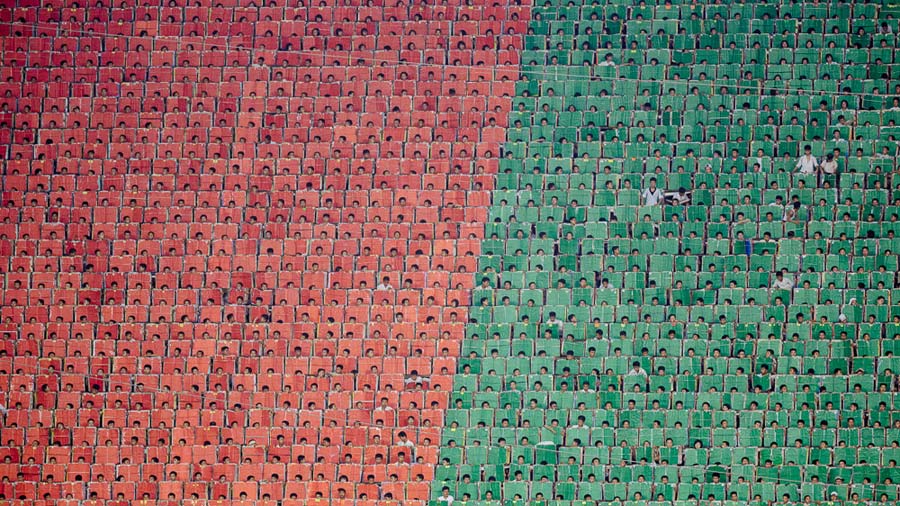

After a quick dinner we drove to Rungrado May Day Stadium. The complex was enormous, yet for an arena that can seat 150,000 people, there were relatively few people outside. My guides traversed the crowd and took me inside. I found my seat, it was unsurprisingly isolated. On the other side of the stadium, tens of thousands of performers warmed up. North Korean youth held books of colored tiles, each acting like a tiny human pixel in a giant array such that, when the tiles in the books were held aloft and displayed, giant images were produced that filled one half of the arena. The youth were practicing before the show began, stomping and yelling in unison as they changed the color of their tiles. The coordination and precision was so furious it made my hair stand on end.

The lights dimmed and thousands of performers streamed onto the green AstroTurf. The show began, narrating the gospel of the Kim family and the history of Korea.

The lights dimmed and thousands of performers streamed onto the green AstroTurf. The show began, narrating the gospel of the Kim family and the history of Korea. The cult surrounding the Kim family is similar to a religion, and takes cues from Christianity. The mass games detail the births and historic acts of both Kim Jong Il and Kim Il Sung. There are many sets to the performance, all are heavily laden with propaganda and teach the viewer about the philosophy of Ju-che – Korean self-reliance and inner strength. A few acts brought moments of levity with performers dressed as farm animals, some were highly militaristic, some involved children who were just as disciplined as the adults. For ninety minutes the 50,000 actors performed each routine with clockwork precision.

The grand finale showed Korea at the center of the world, united to its previous glory. In a perfect world, the South would leave behind its misguided ways and rejoin the North. Only then, could the Korean people become truly strong. Fireworks blasted and the crowd stood and cheered.

The next day I toured Pyongyang with my guides. Mr. Oh dropped us at a fountain downtown and Mr. Lee helped me purchase a bouquet of flowers. We ambled through an empty asphalt lot towards two giant statues: one of President Kim Il Sung the other of Generalissimo Kim Jong Il. A group of Koreans had just stepped off a bus; they too carried bundles of flowers, walking towards the statues to pay their respects. Prior to my arrival, my tour operator explained that I had to pay respect to the leaders when I was in the country, regardless of my personal feelings. It was explained that doing so was similar to entering a mosque, temple or church.

I mixed in with the locals and climbed granite steps as patriotic music piped out of hidden speakers. When the crowd reached the top they organized into a line facing the two statues. I stood with them, feeling grossly out of place at the left end of the line. A guard instructed us to wait, and on a woman’s order the Korean people marched towards the statues and placed their flowers at the base. I mimicked their actions and placed my bouquet at the feet of the bronze statues, then returned to the starting point of the line. The Koreans reassembled and then we all performed one deep, massive bow.

We visited uncountable monuments until late in the afternoon: the Grand People’s Study House, The Juche Tower, The Arch of Triumph, the Workers’ Party Memorial, the Victorious Fatherland Monument – each place we stopped, I’d meet the local monument guide. They would explain the significance of the monument and then I’d have a bit of free time to wander the grounds under their supervision. The propaganda was tiring. Late in the afternoon we left Pyongyang to drive to Nampo City.

By the early evening, we arrived at a gated hotel. I had my own private villa. Previously, Mr. Lee had asked if I would like to have a clam barbecue before dinner, which would cost five Euros extra. I like clams, and decided a barbecue could be fun. He returned from a market outside the hotel grounds with a bag of gray-shelled clams. We all met outside my villa in the parking lot where Mr. Oh prepared an elevated concrete slab with some water. He lined the clams on top of the slab, organizing them into a patterned group, and pulled a small plastic bottle with a yellowish liquid inside from the trunk of the car – kerosene. I watched with hesitation has he generously doused the clams with the fuel and then lit the kerosene soaked clams with his lighter. With a loud whoosh, flames engulfed the clams.

I produced a bottle of scotch I bought from duty free and poured a round of drinks. Mr. Lee, Ms. Won and I squatted on tiny stools and sipped the aged whiskey. For the next thirty minutes Mr. Oh tended to the steaming clams, drizzling more kerosene on them when the flames began to recede. My mind uncomfortably thought of the carcinogens and toxins I’d be ingesting from the kerosene. I drank more scotch.

The clams sizzled and began to open. I could visibly see oil slick rainbows caused by excess kerosene floating on the wet clams.

The clams sizzled and began to open. I could visibly see oil slick rainbows caused by excess kerosene floating on the wet clams. I didn’t want to eat them but knew it would be incredibly rude not to. I hunted and pecked for ones that were sealed tight. I found a closed one and pried it open. I plucked the steaming meat from the shell and popped it in my mouth. The clam was mild, slightly salty. There was a trace of smoky-kerosene that lingered on my palette. Mr. Lee, Ms. Won and Mr. Oh gathered close to the clams and ate them quickly. They didn’t show any concern about ingesting hydrocarbons. Mr. Lee noticed I wasn’t eating that many. He feigned concern but I could tell he wasn’t too worried, the less I ate, the more clams for him.

It rained heavily during the night and it was drizzling still when I checked out. After leaving the hotel, we drove on the large open roads towards Kaesong. The area we drove through was inundated with rain, and much of the infrastructure had been damaged. Bridges had been washed away, roads ruined, farms flooded. The further south we drove the harder the rain came down. We passed pedestrians and bicyclists on the large highways, they were completely soaked.

During the day we toured more sites: the Western Sea Barrage, a large inlet dam that was built in the eighties, a farming co-op and a farmer’s house, another bronze statue of Kim Il Sung. We had to bow before the statue of Kim Il Sung. I was groggy from a bad night’s rest and didn’t put my heart into the bow. Mr. Lee. approached me and grabbed my arm. He asked if I was O.K, saying he had noticed I wasn’t smiling. I couldn’t tell if he was concerned that I wasn’t enjoying the tour, or maybe he thought I wasn’t enjoying his country. Was I being unfairly judged or just completely misinterpreting the behavior of Mr. Lee?

After lunch we had a long haul to Kaesong, the city near the DMZ. The rain continued. We drove through sensitive areas demarcated by Mr. Lee turning around and telling me to put the camera away. We stopped at a nice restaurant for lunch. Women in Hanbok served me, bringing dozens of gold bowls with pickled vegetables and sauces. Mr. Lee said I could order dog soup if I wanted and that it would make me strong if I ate it. Having already sampled dog in China, I decided to pass on the opportunity. Mr. Leefrowned upon my decision and left me alone to eat.

Once he was out of ear shot, Mr. Lee whispered to me “Japanese – Mortal Enemy.” I was a bit surprised, and asked how, as an American, I was classified. “Just Enemy,” he replied with a smile.

My hotel was traditionally styled, the room was bare; just a pad on the floor – no hot water. There was only one other tourist at the hotel, a Japanese man traveling alone. Before dinner, Mr. Lee grabbed my arm as the Japanese man walked passed. Once he was out of ear shot, Mr. Lee whispered to me “Japanese – Mortal Enemy.” I was a bit surprised, and asked how, as an American, I was classified. “Just Enemy,” he replied with a smile.

The next day we travelled further south to the DMZ, arriving by mid-morning. We waited an hour in a small souvenir and snack shop for the tour to start. I spoke with a soldier that had approached me and asked where I was from. When he found out I was American he brought up the Osprey disasters and the failed prototypes a few years ago. I countered, and explained drones to him. No pilots, all robots. He looked worried as he contemplated the idea.

I met my local guide and fell into a group with other Americans. Mr. Lee stayed behind. The tour was brief, stopping at historically significant places along the border. We entered a small building that straddled the 38th parallel. North Korean guards stood by outside. Giant flags of the North and South waved on tall poles on the soil of their respective country. I stepped into South Korea, then back into the North. The local guide corralled some of the wandering tourists and we all returned to the staging area.

On the drive back to Pyongyang we spoke about national politics. Mr. Lee explained the terms that would be required for the South to reunite. I wondered if the two countries had drifted too far apart. The North desperately wanted the South to reunify, but only under their terms. Mr. Lee acknowledged that life was difficult in North Korea. He had exposure to Westerners. He saw foreigners arrive with goods he could never buy, tell about experiences that directly contradicted the official party line. He met and visited with Europeans, Japanese and Americans alike that were genuinely good people. He was in a difficult position, a representative to the outside world for his country, tasked with showing outsiders why the North Korean way, the way of Juche, was righteous and just. Yet, he let on that he knew there were cracks in the immaculate façade.

He was in a difficult position, a representative to the outside world for his country, tasked with showing outsiders why the North Korean way, the way of Juche, was righteous and just.

That evening I had my farewell dinner. It was at a modern tourist restaurant. Dozens of Chinese tourists were celebrating in the main dining room. The hostess escorted us into our private room. I grabbed the scotch and Cohibas I brought from duty free for after the meal. We ate from small plates of food that endlessly arrived from the kitchen. There was too much and I filled up before the main course had even been served. The four of us drank and chatted in the austere white room. I offered everyone a Cohiba, only Mr. Lee took one. He wasn’t sure how to smoke it and I told him not to inhale like a cigarette. ‘Just mouth’ I explained. We lit up and he sucked down the smoke into his lungs, coughing furiously. We chatted for a bit and he told me that I was his first American friend. I wasn’t sure if this was him speaking candidly or if this was a ruse he pulled on all his guests as the tours wound down, North Korean customer service. He extinguished his cigar after smoking half of it, saying he was feeling sick. I regretted smoking a whole one myself.

In the morning I checked out of the hotel and then we visited the Pyongyang metro. Mr. Lee said it is the deepest metro in the world. I heard the same about the metro in Kiev. The escalator moved at a breakneck pace and was very long. The people riding the opposite escalator stared with unrelenting focus as I passed on my way down. I’d smile but only receive the same serious stare in return. The designs of the stations were typical soviet era vaults, except these had the most decoration of any I’d seen.

The trains were simple. The interiors were bare, no advertisements, only faux wood paneling and the portraits of the Kims. When the train travelled everyone just looked at their feet or stared at me, not too different from other metros where riders sit silently and stare at their phones.

We went back to the hotel to the revolving restaurant at the top floor of the building. The space had panorama vistas of Pyongyang. We were a bit early and Mr. Lee sat me at my table, saying he’d return in an hour. I gazed out the window; it didn’t look like the restaurant was revolving. I asked Mr. Lee and he said that we were indeed rotating. I lined up a pane of one of the windows with a building in the distance. They stayed in line. I insisted we were not revolving; Mr. Lee assured me we were. I took out my camera, set it on the table and took a picture. Without moving it I took another photo thirty seconds later and then cycled between the two on the playback screen. They were identical. Mr. Lee changed tactics and acted surprised that I wanted the revolving restaurant to revolve. I told him I’d like it to if it was possible. He left to a back room and I heard loud arguing in Korean. Suddenly, sounds of gnashing gears and scraping metal echoed from somewhere below and the restaurant slowly began to rotate. Mr. Lee returned with a smile. “Now we are spinning,” he said rubbing his hands together. I thanked him and he left. I ate my lunch alone, sitting forty-five floors above the city, slowly rotating about the panorama of Pyongyang.

That afternoon we left for the airport. Though the drive took some time, we still arrived early. There was only a waiting room after security so Mr. Lee, Ms. Won and Mr. Oh and I all went into a nearby café. I bought a round of cokes. I was sad to be parting from the group. Mr. Lee had an interest in the outside world, though he hid it well; he often would ask me what things were like in other countries. During the tour I showed him pictures of other places I had been. I wondered if he genuinely considered me a friend. We had joked in the car during the long drives and I felt that he became more candid over the days. Could he consider an enemy a friend? Ms. Won would do well for herself. She was attractive, educated, and Mr. Lee had told me she had a boyfriend that was successful in the party. Mr. Oh never spoke, and rarely showed emotion. He was hard working, dodging potholes on the road, often the only person awake during the journey. The happiest I saw him was when we’d barbecued clams.

He was hard working, dodging potholes on the road, often the only person awake during the journey. The happiest I saw him was when we’d barbecued clams.

After thirty minutes I said goodbye to my guides. I hugged them all, probably a faux pas. I passed through security and retrieved my phone. It was dead, but otherwise just as I had left it. I sat in the bare hall and waited for my flight to China.

Images and story by Porter Yates

Receive a postcard from us sign up