Jonathon Collins is a scientist, photographer, writer and storyteller with an interest in the ever-changing layers of the human condition.

Where are you based?

At the moment I’m based out of a backpack in South America, but the place I call home is the beautiful city of Sydney, Australia.

How do you make a living?

I am an environmental scientist, so the majority of my income comes from a fulltime job, and I try to pick up freelance photography or social media work on the side as a creative outlet. While many people assume differently, 90% of my travels so far have been the result of working hard, being a frugal saver and then hard core budgeting while I’m on the road. I have literally no financial assets to show for my life so far, but I have never regretted a single dollar spent on travelling.

What are you motivated by?

Since I was young, I have always been motivated by my own curiosity to explore other landscapes, other contexts and other lives. This curiosity has manifested in my photography and writing, as my inspiration always comes from telling stories or experiences from places or people that might otherwise go untold.

Above: A dawn hike in pouring rain and a blanket of fog to the base of the falls meant not a single person for kilometres. It was a fleeting moment of wild and rugged beauty in the Blue Mountains of New South Wales, Australia.

What’s been your most memorable project to date?

From January to April this year, I began working on my own project ‘The Human Tide’, which is an ongoing piece portraying the impacts of climate change on vulnerable communities. For the first chapter, I lived and documented the lives of cattle herders in the Sahel of West Africa, and with nomadic fishermen in the Coral Triangle in Southeast Asia. It was truly humbling to be welcomed into two very different communities, and opened my eyes to the turmoil these marginalised communities are set to face in the near future.

Above: Alongside more than 150 million others in the Coral Triangle region; the Bajau people rely solely on the abundance and diversity of the surrounding marine resources for their survival. However, throughout the region a common theme is playing out as marine species are declining at a rapid pace. Warming sea surface temperatures, ocean acidification, increased storm intensity and sea level rise will see the region’s ability to feed coastal subsistence communities decline by 80%.

What do you take with you on your travels?

My backpack seems to get heavier and heavier with an ever growing interest in photography. I carry three cameras; an Olympus PEN-F and two of the Olympus OM-D series, as well as a range of fixed lenses. I have the underwater case for the OM-D EM-5, a Mavic Pro drone, Macbook, two hardrives and a million spare batteries because I usually end up in places with no electricity. As far as other essentials, I’m always carrying a notebook, mosquito spray and an endless supply of colourful socks.

Above: In Malaysia, the Bajau are denied the right to any legal documents and are by default, stateless. Many cases were recounted of Bajau families being deported to the Philippines despite having lived in Malaysia for over three generations. With limited capacity to adapt or alleviate themselves from this complex cycle, the Bajau have begun migrating as a necessary survival tactic; abandoning their tradition of living primarily off the ocean.

What impact has travel made on your life?

Travelling has opened my heart and mind to the world and the lessons it has to offer. Over the years, travel has taught me immense patience through various trials and tribulations, strength in times of loneliness, and the overall resilience of the human spirit when you are open to people whose path intersects with your own.

Above: In addition to the widespread impacts of climate change, the booming coastal population of Asia, as well as a growing demand for live export in Mainland China and Hong Kong has seen the continued use of unsustainable fishing practices like cyanide fishing and dynamite blasts which diminish the region’s marine ecosystem further. It has become yet another virtuous cycle of subsistence communities depleting the very environment that sustains them in order to survive.

What make up the best parts of an adventure?

The greatest part of any adventure is the unknown. A real adventures comes from no plan, spontaneity in decision-making, meeting people from all walks of life, interacting with cultures or religions that you previously haven’t, and a sense of resetting your life with each new place or journey. I love that when when you travel you feel like you have lived a year in a single day, just by simply saying ‘yes’ to each opportunity that comes your way.

Above: The Danakil Depression is located in the Afar region of northern Ethiopia, an area which bears the title of being the year-round hottest place on Earth, and one of the lowest depressions on the planet. Such harsh conditions see almost no rainfall during the year and temperatures reaching as hot as 65 degrees celsius in Summer. Laying more than 100m below sea level, Lake Asale is a result of the Awash river draining into the Danakil but never reaching the Indian Ocean. In the evening the lake, a shallow layer of water atop crystalline salt perfectly reflects the sky.

What advice do you have for aspiring photographers?

Photography is one of the most powerful and infinite art forms to tell a story; whether it be your own or someone else’s. Remember that whatever you create will always have meaning to someone in the world, and most importantly, believe in the story you are telling. Every click of that shutter becomes a memory for someone.

Above: Across the desolate landscape, temperatures soar well above 40°C and the sky is a constant haze of unsettled dust. The horizon line is barren, with only a handful of scattered trees and mud huts providing salvation from the harsh sun. The Sahel is one of the harshest places to live on Earth. The narrow strip of land stretches across fourteen countries in northern Africa, where communities from a number of different ethnic groups have adapted to its extreme living conditions over time.

Anything else you’d like to share?

Travel has taught me a fundamental truth to this world. Regardless of where you are born, what life you have lived, or the choices you have made; we are all the same. Take the time to discover something that feels ‘different’ and you will soon realise how similar we are as humans.

Above: Over the last half a century, the Sahel has faced the most severe and long enduring drought events than anywhere else on the planet. Now, the region faces its greatest challenge to date; erratic rainfall and increasing desertification at the onset of climate change and increased land use, whereby the Sahara is advancing in many cases by more than 10km every year. For the pastoral, agricultural and nomadic communities of the Sahel, the risk of resource scarcity is one which also brings a likelihood of severe famine, instability, conflict and forced migration.

Above: While the Fulani people of the Sahel, now face their greatest challenge to date with the ongoing impacts of a changing climate; they, like many others in the region have already adapted to the most extreme living conditions in the world. This is not to say that they are more or less vulnerable to climate change, but have shown that through periods of great adversity that it is possible to overcome hardships through nothing but mobility and ingenuity to their methods. It has now been almost three decades of prolonged drought and inconsistent rain, versus a lifetime of hope and resilience.

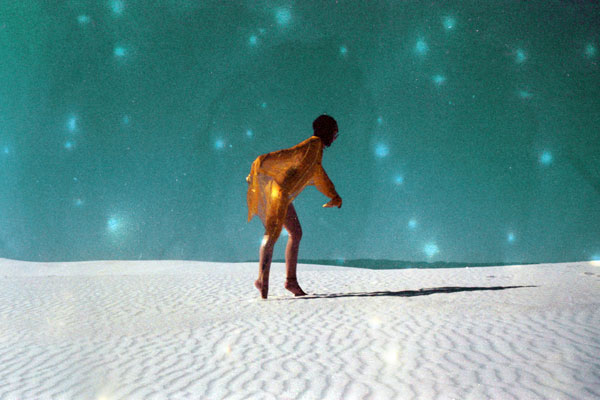

Above: Pulsing networks, invisible currents, life carried through ebbs and flows. It communicates with every sense in overdrive. A feeling that is as spiritual as it is physical, from the symbiotic connection between man and the wide expanse of water that most of us know so little about. The discourse of their whole lives revolve around a connection with the ocean; their livelihoods, their fate, their survival.

Receive a postcard from us sign up