Reuben Wu is an example of how hard work mixed with a restless mind can lead to endless creative potential. Floating between directing, photography and playing in his band Ladytron, Reuben’s been able to develop his creative process in a way that is unrestricted by medium or format.

It’s not all a creative genius-type fantasy though; in order to create such unique landscape photographs requires exhaustive planning, research, experimentation and hard-headedness. We could all learn a thing or two from Reuben, so we recently sat down with him to do just that. Turns out he’s also a classically trained violinist…

You’ve been to some pretty mind-blowing spots around the world and have been able to tell some amazing stories through your pictures. What about the stories behind the frames? Can you tell us about a ‘what the hell have I gotten myself into’ moment?’, that happened on one of your adventures?

I think the most trouble I got into was when I went to look for an abandoned amusement park on top of a mountain outside of Bilbao in Spain. My band was on tour and we had a bit of time between arriving and soundcheck, so I took a cab to the location (which was in the middle of nowhere and devoid of people) and had him leave me for a couple of hours. I ended up jumping the fence of this spooky park, which had been abandoned since the 1980s and wandered around for about ten minutes until I spotted some movement in the undergrowth. What I assumed was a small animal turned out to be an angry armed guard with two Rottweilers, demanding my papers and threatening to set his dogs on me. I remember thinking to myself, ’This would be very bad if the concert got cancelled because I was arrested for trespassing or attacked by dogs’. In the end I think it was the fact I told him I was a travelling musician from Liverpool which got me off the hook because he begrudgingly said he liked the Beatles before turfing me out of the premises. Since then I am a bit more careful about where I venture with my camera.

I experimented a lot with film types and old cameras when I was learning a few years ago, inspired by that vintage film look and shooting places which jarred with that aesthetic and process: immense space age technology or abandoned Arctic townships.

How did you find, and continue to develop your aesthetic?

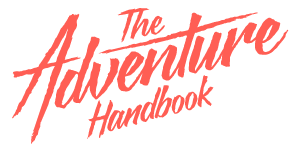

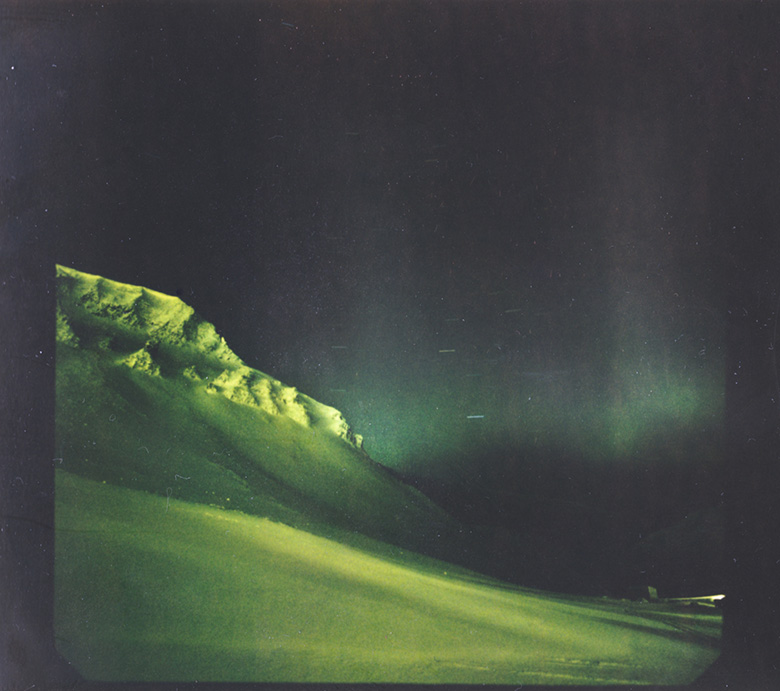

In the beginning, a lot of it had to do with anachronism in medium and subject. I experimented a lot with film types and old cameras when I was learning a few years ago, inspired by that vintage film look and shooting places which jarred with that aesthetic and process: immense space age technology or abandoned Arctic townships. I wanted to document these places and things in a way that had never been done before, like shooting the northern lights with expired Polaroid film, so in a way it was a lot about the process. Since then I continue the same aesthetic but it is more refined and makes more sense to me. I see the work as not just photography, but a craft of visual art.

What can you tell us about the role of preparation and chance in your work?

I prepare as much as I can, especially when a place is hard to access or off the beaten track. This includes having a GPS enabled phone with maps, figuring out the direction and phase of the sun and moon cycles, planning angles of attack and choice of gear for the type of picture I want to capture. When I shoot personal work, I am pretty much up all night so I allow for time to experiment and for serendipity to happen. I think going back to a place and shooting it again is a great way to improve because you have already processed how you would shoot it better, and each time you discover something new.

A photograph is limited by the tools you use; colour depth, sensors, lens distortion to name a few variables. Then there are editing programs to help retouch, manipulate and produce the raw frame. How do the various physical and digital processes work with the way you do things to produce the final frame?

Photography is a fiction. It’s a frame of a film which hasn’t been made, or a line from a forgotten poem. I always create in camera as much as possible, because it is also about the experience of what is in front of you at the time. The tools you use to portray your vision don’t really matter but I’m not afraid to intertwine techniques of the physical with digital tools as long as the intended picture is made successfully.

I think going back to a place and shooting it again is a great way to improve because you have already processed how you would shoot it better, and each time you discover something new.

Your work makes me think of a beautiful, imaginary future world as much as it does a decaying, catastrophic one. Is this intentional?

Yes, I seem unable to escape the hints of melancholy in my work. Sometimes it’s very subtle, others not at all, but it is general attribute I am always drawn to in art.

Photography is a fiction. It’s a frame of a film which hasn’t been made, or a line from a forgotten poem.

New technologies such as 360 degree cameras and drones are taking photography to (literally) new heights. What’s the difference between using these new tools as a gimmick versus using them to innovate and push boundaries?

I think when a technology is new, people are playing and exploring possibilities, and this is a crucial beginning for creativity. Initially these ideas can be gimmicky but eventually the familiarity with the new tool allows you to make new connections in your mind. The novelty of piloting a drone or using a 360 camera begins to fade away and you are simply left with an opportunity to make deeper and more meaningful concepts real.

Receive a postcard from us sign up