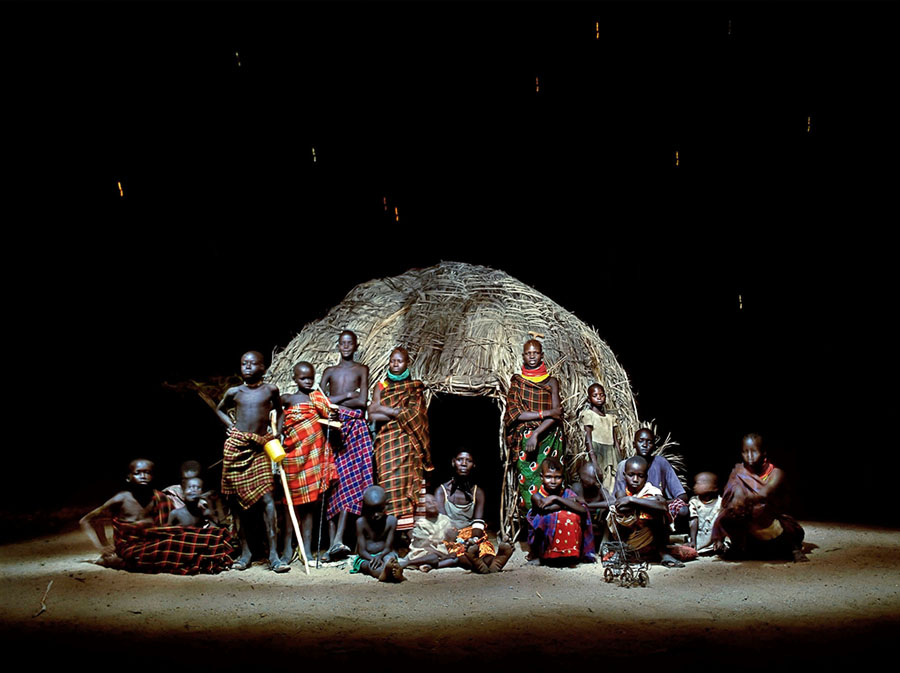

You can’t really say Argentinian photographer Alejandro Chaskielberg simply ‘takes’ photographs.

He is a photographer, but his work is cinematic. Like a magician, there are smoke and mirrors, there is darkness, full moon, mysticism. There is also revelation; these photographs are largely recreations that border the figurative and literal, representing the toil and real life of people in living in remote villages or communities. Often his work deals with struggle, yet there is strength and beauty in every image. What is effectively distilled is vitality of humanity and nature.

Often his work deals with struggle, yet there is strength and beauty in every image. What is effectively distilled is the vitality of humanity and nature.

How emotional his own work makes him makes an impression. There is a real sense of commitment, time spent seeking, learning and earning the trust of the people he engages to create each work. “When I made my first book, I made 55 images in 3 years. It’s a different approach than nowadays.” He spoke with AHB about photography and travel, and dedication to pursuing what you love.

What draws you to photography as a method of expression?

I think photography is very instinctive for me because I got involved with it when I was 10 years old. I couldn’t communicate too much with people because I was very shy, and a very solitary young man. Photography was the best way to express myself.

Basically I love the object of the camera, the machine. When I was 18 and I had to start working, the only thing I was doing was photography. So that was very easy for me to start doing what I was already doing all day, just taking photos.

I studied cinematography in Film school here in Buenos Aires, at the National Institute of Cinematography. So I am a Director of Photography, or a cinematographer

People and their relationship to the environment is a major component of your work. What draws you to this thematically?

I sometimes think of myself as an environmental portraitist, basically I take portraits of people in landscapes. I think nature is so rich in colours and shapes; indoor photography takes too much time and effort to try to create some kind image. When you’re outside and you see nature, everything is there. You don’t have to force it.

I am in love with colours and I am in love with the natural process of light. Sometimes I spend days until I find a good time to take a picture. I am like a more old fashioned photographer, trying to wait for the correct light.

I am in love with colours and I am in love with the natural process of light. Sometimes I spend days until I find a good time to take a picture.

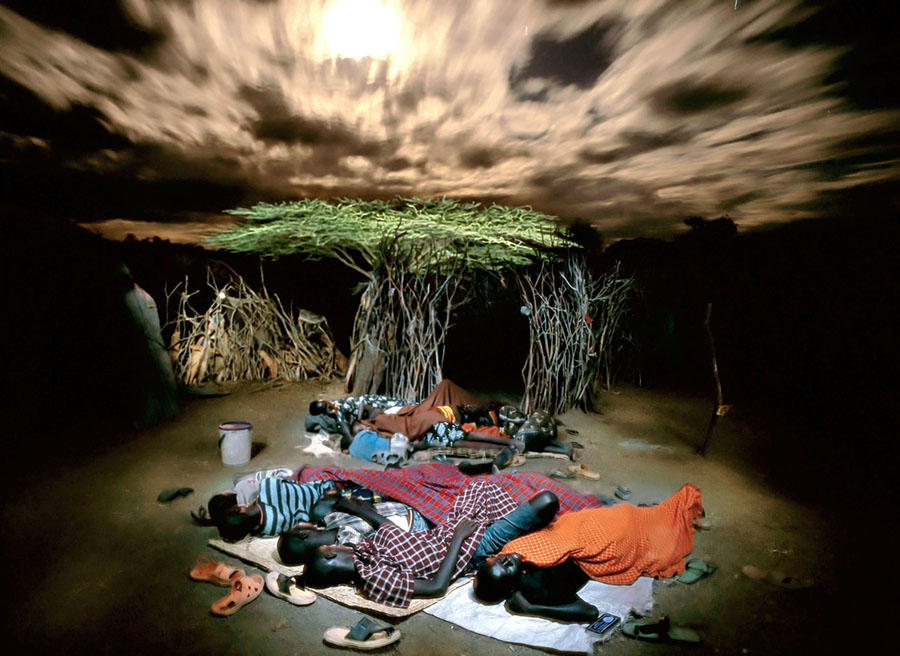

You largely take photographs in the dead of night, recreating scenes from the day. Can you explain how you do this?

Before I go to the location, I research where the moon is going to rise at what time, the position, and I try to imagine the whole scene. If the place doesn’t have too much artificial light, I try to use the moonlight as the main light source to illuminate the background.

When I did La Creciente (the ‘high tide’ in English) with the islanders living on the Paraná River Delta, I had some rehearsals with the people before using the camera in the dark. First of all, I just followed the people, sharing daily life with them so they didn’t get nervous with the camera. And then at one point I told them I wanted to repeat this at night. What I do is actually capture the image with my eyes, and then repeat everything in front of the camera.

There are various dichotomies in your practice, but namely your subject are real people in recreated scenarios.

In a way, I don’t want to say this is fiction or is this reality: we are taking pictures, we are not showing the reality. It’s like a painter from an ancient era. When you see a painting, you don’t think is it fiction or real, but that we can learn from medieval painters or renaissance painters about our past, culture. Of course it’s an impression of someone’s, an impression of reality. I think of my photography in the same way.

There is definitely a sense these are photographs for exhibition, than the archives.

I think that I do documentary photography, but with a personal approach. Real or fiction – these are definitions I don’t trust too much. But of course I say this is documentary, because you learn about the people, the people are real and the situation is real.

Does travel and exploration of new places play a big part in your projects?

Yes, of course. I cannot separate them. I get inspired when I travel and actually my personal approach with photography began when I started travelling, when I was camping in Uruguay and started taking pictures for Nocturana. I don’t know why, but it’s so hard for me to take pictures in Buenos Aires. I prefer to travel and discover my own photography working outside home.

Does that have something to do with being out of the city as well? Do you find having more space, being in nature, engages you creatively?

Yes, but it’s not only to do with a change of scenery. When you travel everything changes. You recreate yourself as you want, you can be an entirely new person. I love that first impression you have within a city or landscape when you see it for the first time. It’s not only nature but it’s more like the adventure that you are involved in makes you feel different. And because you feel different, you photograph in a different way.

And the long process of learning about people, as they go from strangers to subjects and friends.

For me, shooting complete strangers is more difficult that shooting people you know. I would say most of the people pictured in La Creciente are my friends now. To create a beautiful image of someone is not very difficult, but to try to capture an image that talks about people, it’s more difficult. It was difficult to get people to accept going into the forest and river at night. So I had to become their friend. They had to trust me. In the beginning, they thought it was a crazy idea.

To create a beautiful image of someone is not very difficult, but to try to capture an image that talks about people, it’s more difficult.

It crossed my mind – it’s impressive people agree to do this.

But that’s why! The river is a network of rivers, and also of relationships. I had to become a part of that, get connected to one islander who is related to someone over the way, who can introduce me to a hunter who lives alone in the woodlands.

Your last project was in Otsuchi, a village in Japan that was devastated by the tsunami in 2011. There is pain and destruction in the images, also a measure of quietude… I see here more than ever here a surreal aspect of your work, did it feel ‘surreal’ taking the photos?

In Otsuchi I didn’t see anything ‘surreal’. When I arrived there I felt very sad, because of being in a destroyed city, where many people died. This kind of project, where you’re working in the aftermath of a tragedy, what can you do with photography? I came from the other side of the world, from Argentina, there is no place farther away from my hometown than Otsuchi.

I travelled 3 times to Otsuchi. I started by taking photographs of survivors using black and white film. I found a family album that was completely destroyed by the water; when I saw that album in that first trip, I realised that you can see all the destruction of the city in just in a simple family album. Because of the corrosion of the water. all of the colours of the album had mixed. There were new colours, new blues and new yellows that weren’t in the original pictures. I built colour pallets with these images and applied it to my own black and white images. For me conceptually, the colour was like a new survivor of the tragedy.

Everyone saw what had happened in Japan in 2011 but I think we forget these kinds of things easily. Now I’m doing a book, and a book remains forever. I trust in that.

Receive a postcard from us sign up