AHB were a little nervous to meet up with Ingvar Kenne, Swedish-born Sydney-based photographer, best known for his signature square-framed portraits. There is something beyond four equal sides that makes his photographs perfect somehow… For an artist at loathe to extrapolate too much on exactly what his photographs mean, there are plenty of ‘somethings’ and ‘somehows’ – usually ‘somewhere’s too – at play. Teas and coffees on the table, we got stuck into it.

You’re a bit of an everywhere man, travelled far and wide, emigrated from your home country – we’re interested, what does adventure mean to you?

For me I think I always challenged myself, as far as travel goes, I like to see things through. Adventure is more for yourself than anything. For me, climbing a mountain was one of my biggest moments. I mean, if you’re a mountaineer that means nothing, this was just 1000 metres, but it was a hard scramble up, I was on my own… Adventure is when you excel on what you knew previously. Go outside your boundaries that you’re very used to and you try something that you’ve never done before.

Has your taste for adventure changed with experience?

Yeah I think what’s happened is that I can’t practice my own adventures, and haven’t been able to since I had a family really. My work takes me places for a short stint; it took me to prison in New Zealand. I’d never been in a prison before.It’s interesting, you still get confronted – in a good way – just seeing things.

But I haven’t been able to do that kind of adventure – pre-email, where you kind of give away your apartment, you pack everything in boxes and chuck it in the basement at your parents and you say, “I’ll be back.” Choosing to switch off for six months, that type of adventure is long gone, I think. You’d have to be a monk to do that.

So you grew up in Sweden, and left when you were twenty-something to go on the trip that became Chasing Summer. Had you travelled like this, to that extent, before?

Yeah, it was my third big trip. (The first) was in ‘87, I went around Australia and New Zealand hitchhiking. I wanted to go home after a week, I was dead scared, in some Kings Cross hostel. Some Swedish kids had done train-hopping around Europe, but I never did it. I went north, trekking mountains instead.

I was dead scared, in some Kings Cross hostel. Some Swedish kids had done train-hopping around Europe, but I never did it.

I got back and managed to get into photo university with the work from that trip. I did 3 years there, saved a little money somehow and then went back to New Zealand with my girlfriend at the time. We bought horses and rode across the Southern Alps on horseback for 2 months.

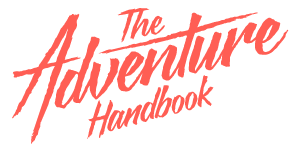

My horse went lame, and we had to give them away. The entire trip lasted a year, and that’s when I went to India, and Nepal. To Ladakh.

That was your top of the mountain moment.

It was 5 years all that time. Go back home, cash up, and leave again. And not really committing to being a photographer. I felt like I’d sort of wasted a lot of opportunities photographically, so I wanted to be focussed during (Chasing Summer).

I think it’s so easy to be a photographer and always talk about projects and ideas but forget to take the photographs. Without them you got nothing to discuss. You can’t even talk about whatever you’re up to, because you’re only thinking. You’ve got to take the photos.

I’ve read about the careful consideration you give to the composition of your frame, but that for Citizen, you didn’t really have a clear idea of what it was going to be… Is your process kind of an amalgam of the two, embracing randomness but providing structure?

I think that’s a good way to sum it up. Obviously each project is different. In Chasing Summer, I kind of realised what it was half way through, I just kept taking pictures of people. I got proof sheets sent to me every 3 months so I knew where it was heading and the focus was there. Citizen is a totally different beast.

When I got here 20 years ago, I started working as a waiter because I didn’t know anyone. All I had to show for myself was this box of portraits from my trips. After 3 years I finally got into some magazines, a few portraits here and there. So many people didn’t like it, but I was lucky there were a few people who did… All I ended up doing was adding more photographs with the same parameters.

When I got here 20 years ago, I started working as a waiter because I didn’t know anyone. All I had to show for myself was this box of portraits from my trips.

Citizen, the genesis, or the idea of it, came about when the work dried up because people didn’t want me to shoot film anymore but digital, or they tried to art direct it. So I stopped working for people, after 10 years. I started looking back at what I had and realised this is just an extension of Chasing Summer. Put those photographs with Citizen and mix ’em around people wouldn’t think its out of place. So that’s when I thought, let’s try to put it together in a book.

So your style is pretty much coming out of that one trip from Sweden, and that one book.

I think that (Chasing Summer) formed me completely as a photographer. I think it came from the luxury of being away from everything you knew for so long, and pop culture. I never watched television during that time, read magazines, I was just in my own head. It wasn’t a discussion with anyone else but myself. Maybe that’s why it became quite defined in that time.

You don’t bark into situations – you can, but you’re going to get rejected or end up in trouble.

What did you learn, from that trip and the focus?

I was naturally shy, and that was the biggest thing. I had a lot of fear. If it taught me anything it was just to handle people better. You don’t know what you’re gonna eat, or where you’re gonna sleep, or who you can trust. You’re senses are heightened when you travel, that’s why it’s so fun.

You have to pull back sometimes. I never got a no, probably because there was an ‘ok’ floating around there before I even asked. They’ve looked at you, or they’ve smiled quickly at you, and it’s going be good. You don’t bark into situations – you can, but you’re going to get rejected or end up in trouble.

We get asked often about the relationship between travel and privilege. That’s exactly what I see travel as, in terms of adventure, people don’t do it out of necessity but luxury almost, and opportunity. When the subject of your photograph might be underprivileged somehow, and you are documenting that in the form of a portrait, what is your take on that experience?

I use that same word when I talk about travel – luxury. It’s such a white man’s headache you know, like, it’s not hard. People say “How did you do that? That’s so hard.” And I think, “Well there are some cold days, some warm days, you know..” But it’s my own choice, and it’s a privilege entirely.

I think my interpretation of that person at that moment in that location is kind of as simple as I can explain it.

When I tried to catalogue Citizen, everything was so different. Baz Luhrman, Malcolm Fraser, a prostitute, and then a child sex-offender… To me it’s that moment, the reason I photographed you and what you were to me when I met you. Surely, there is more to them as a person but I don’t know that. Some of the meetings, it’s five minutes. Six frames and we all move on.

I think my interpretation of that person at that moment in that location is kind of as simple as I can explain it. I don’t try to tell anything. I think I try to communicate with myself more than anything.

Does the time that you spend and the energy that you share with someone have an affect on the portrait?

I think I’m pretty controlling. I see something and that’s my square. And then I just wait for someone to come around and say, “Can I take your portrait?” If you control the environment that you want to put someone in, I can be really loose and free with them. You know that everything around them is taken care of. Now I can just look at what they do. While I talk to people, I get to look at them closely. People do things all the time that are great. I add that back in because that’s what I want to photograph but, you know, I was too slow.

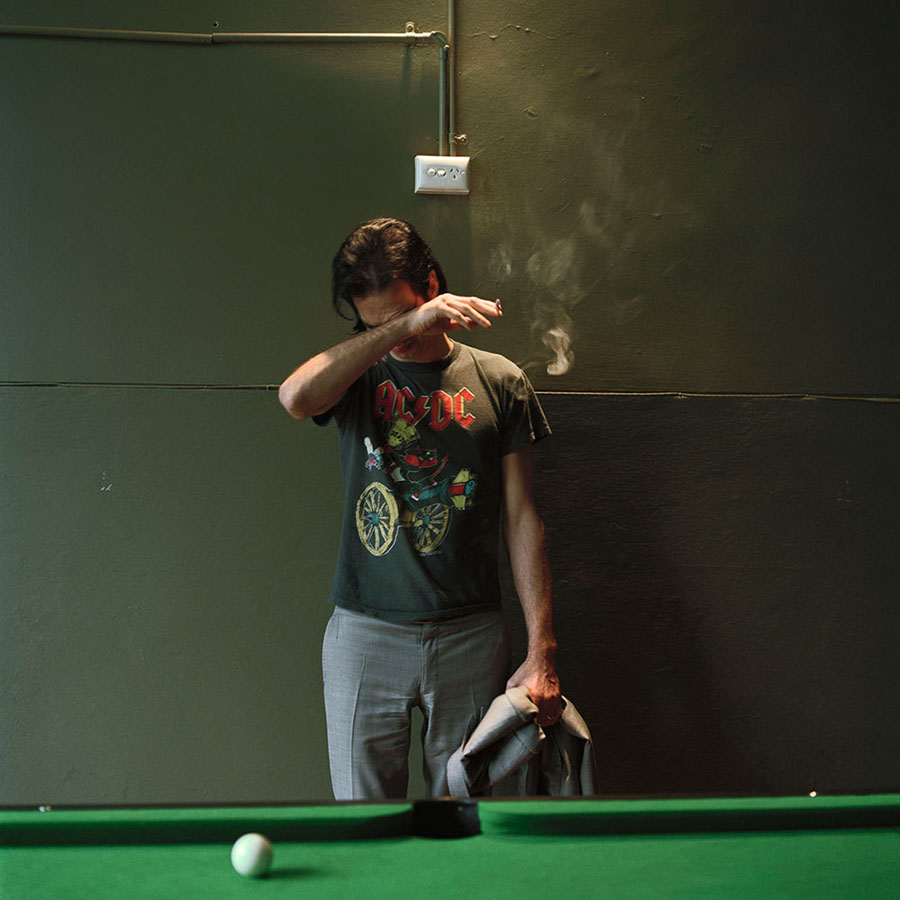

Nick Cave, Musician, Melbourne, Australia, 2001

Leanne & Wendell, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada

Angus Young, Musician, Sydney, Australia, 2003

Lets talk about squares. Not only do you photograph within a square frame, often, but it’s rather popular these days.

Instagram, damn them. If I could sue them I could!

After the army, I ended up working in Hasselblad, the Swedish camera manufacturer, joining cog wheels and stuff. I ended up acquiring a cheap camera because I was staff. So that’s the square, the Hasselblad 503, 500. A lot of master photographers at the time used these cameras, Irving Penn for instance. Having one of those, getting one of those in my hand, I loved it.

Now I look at things and it’s just a line going around a square crop – the one lens, one camera, and I just like it. It’s calming I guess, the four equal sides. You can fill it from any which way so many times over and it’s endless. It’s like Sudoku, you know, all different solutions.

I was hoping to ask about the introduction to Chasing Summer – written by Paul Theroux. Why precede the book with an essay?

I found his literary publisher in New York and sent him a copy – and then 911 happened that week. Then there was the Anthrax scare. A year later, he’d been in Africa researching his next book, he came back and found the book and loved it. He said he didn’t have time to write something, he was trying to write a novel, but there were three short story books. “Use anything you want.”

I think I was hell bent on having someone that looked upon travel in some way that you can’t read in my photographs. I wanted a take on the experience of travel and letting go, and what he wrote just suited it perfectly.

ingvarkenne.com | @ingvarkenne

Interview by Ben and Emilia for AHB

Receive a postcard from us sign up