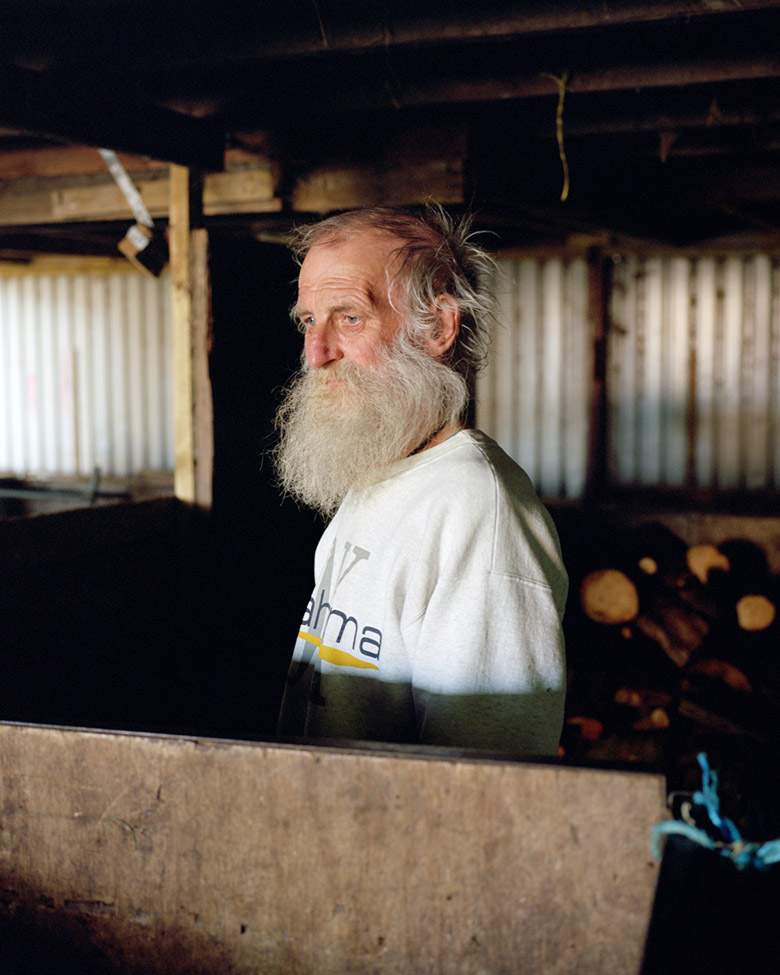

Mat Hay is a prolific photographer fascinated with the relationship shared between humans, animals, and the land. His vocation has taken him across the globe to the likes of Europe, North America, and the U.K. His latest exhibition, Heather Burn, draws upon all of his resources as a photographer as Mat attempts to document life in his home country, Scotland. A country that is at times desolate and barren, Mat brings to the spotlight the unassuming beauty hidden in the Scottish hinterland, finding some of the most refined jewels in the mundane.

You’ve worked across Europe, North America, and your most recent project, examining life in Scotland’s Central Highlands, adds the U.K to your travel portfolio. What separates the U.K. (specifically Scotland) from the rest of the world?

Probably the most obvious difference is the people and the character of the nation. It’s hard to define with words exactly, but the attitude and sense of humor of Scotland really distinguishes it from other places.

Talking about your Central Highlands project you have said the work “seeks to address the disparity between the experience of life here and the prevailing image of rural Scotland, which is dominated by historical context and nostalgia.” Can you explain this quote? Why is it so important for you to address this disparity?

A while ago I realized that my experience of Scotland, having grown up here, was quite different from how it’s represented and how people view it from outside, specifically in regards to the rural areas. And this concerned me. A lot of it has to do with tourism and marketing Scotland and its products as a brand. The country has such a rich and interesting history, but it can be hard to look beyond and it’s easy to romanticize. Artists often use it as a kind of default source of subject matter too, which I fully understand and isn’t necessarily negative. But if I wasn’t able to connect with the image and culture of my own country, then I had to find out why and resolve it in some way.

“…having grown up here, was quite different from how it’s represented and how people view it from outside, specifically in regards to the rural areas. And this concerned me.”

Studying photography at University I found I could relate more to photographic representations of other countries, in particular the U.S. and Canada. Then I noticed they actually share a lot of similarities with Scotland (for instance with culture, architecture, wildlife, geology etc..), but they have been photographed quite differently. In particular, artists documenting North America seem more interested in the present rather than the past. So, I was intrigued by this and decided to start exploring my own ideas about how Scotland could be shown, using North America as a reference point. Of course, there are some excellent representations of modern Scotland, but it seemed there was room for a different voice, particularly when talking about the Highlands

There is a theme that resonates throughout the project: you seem to highlight the close and almost inseparable relationship shared between people, animals, and the environment. Why is it so important to focus on this connection?

As city-dwellers, we can see animals and countryside, but we really have very little grasp of how humans actually live outside of a city, and what our relationship with nature is. So it’s refreshing to see it in action. The people in this project are tuned in and rely on what the environment is telling them, and are so directly affected by what animals can offer and what animals need in return. Importantly though, examining this also reminds us how we have effected and manipulated the natural world. In Scotland for instance, there is often an image that the country is wild and untamed. Indeed, there may be a few small pockets like this out there, but really we have completely changed the natural world to suit our needs. It can be fascinating to observe our achievements as a species. But it also serves to remind us urbanites what incredible pressure humans put on the environment.

Being born in Scotland, this project must have been personal for you. Did your travelling experience, over the three years of shooting the project, challenge or reshape your understanding of the country? How?

Yes definitely. And that was one of the main reasons for embarking on the project. I always thought after I got my degree I would leave Scotland to live abroad and see what the rest of the world had to offer. But I was conscious that deep down I didn’t really know my own country yet, and so decided to try and establish a more informed and personal relationship with it. This then helped me realise that my experience of Scotland wasn’t the same as the prevailing image of it, either at home or abroad. And so in general, what this project represents is all the new things I’ve observed and learned about my country during the time I’ve spent exploring it.

Take me through your three years of road tripping. Which parts of Scotland did you visit? Did you come across any memorable characters? What are a few of the most memorable places?

I travelled throughout the heart of Scotland, in the Highlands, pretty much in a triangle between Perth, Inverness, and Fort William, but the biggest proportion of the project comes from a lesser known Glen in Perthshire. My brother and his family lived there for a while, running a small post office and tea room, which made it a good access point into the Highlands, and reachable in about three hours. The glen is huge and, like most secluded areas of Scotland, has an amazing mix of characters, stories, and industry.

“I was conscious that deep down I didn’t really know my own country yet, and so decided to try and establish a more informed and personal relationship with it.”

Pretty much everything in the project has an interesting story behind it, but one of the most memorable places I visited was this almost ‘secret’ glen near Loch Ness that I was told about by someone I’ve photographed a lot. Again, its huge, but very little people know about it and you even have to register at a gatehouse to get access. Its home to one of the very few remaining sections of the Caledonian Forrest and a truly beautiful place to visit. But like a lot of glens it has a series of hydroelectric structures in place, with a dam and reservoir at one end, which I photographed because of its impressive, brutal concrete design. It’s a really intriguing place, and had pretty much everything I was looking for.

You said you shadowed people, strangers at times, to capture a truer picture of their lives. How did people generally react to being followed? Any experiences that stand out?

People are generally pretty good about being photographed, once you give them some background to you and your project, and they’ve had a think about who you are. Being able to give them a point of reference, like mentioning my brother and his post office, or name dropping one of the other people I’ve photographed is always really helpful. Then if I can get my hands dirty by helping out around their home or farm, that usually helps show that I’m in it for the experience. And people tend to like having a visitor from outside their area who is taking an interest in their lifestyle.

“…if I can get my hands dirty by helping out around their home or farm, that usually helps show that I’m in it for the experience. And people tend to like having a visitor from outside their area who is taking an interest in their lifestyle.”

Two of the nicest people I’ve met are these shepherds, Iain and Cathy, from Colonsay and Oklahoma respectively, who I’ve visited and photographed several times. They are a lovely couple, who immediately welcomed me in. They accommodated my sometimes bizarre requests and instructions for doing photos and were always enthusiastic. Now if I’m in the area I will usually come across them rounding up sheep, or I’ll drop in to their farm with some biscuits and have a cup of tea. They’re always interested in hearing what I’ve been up to and likewise, it’s great to hear how they’ve been progressing through each season with the farm and their animals.

You slept in spare rooms in exchange for chores or photographs. Describe for me how these situations came about (i.e. was it with a family? What region did they live in? etc).

It usually takes a while to get to the point of staying at someone’s house, although highland people are so hospitable there are constant offers, often from complete strangers. I hate to impose though. I feel I am already asking a lot of them being in the photos. However, there has been one particular family who have been such an incredible support to me over the years. A lovely couple with two kids who have a small domestic farm and little rental cottage that they are happy for me to use when its empty. In return I’ll maybe help out with chores or look after their dog during holidays. Mostly I think they just like the fact I arrive with wine and cheese and offer a perspective of life outside of the glen. And I think we all appreciate our now customary nightly in-depth discussions over the kitchen table! (One is a journalist and the other studying psychotherapy, so I always need to put my brain in to gear)

You spent days alone hiking and driving along the roads. Are you someone who feels lonely at times when they’re travelling?

Yeah for sure, there are times when you want to share your experiences, to talk about places and people that you’ve come across with someone you know, or have the support of someone you trust right there with you to bounce ideas off. But being a photographer working on a project like this requires you to have freedom of movement and to be able to take actions without hesitation or consideration for people you’ve brought along. Having non-photographers on board would just cause friction. I’m also pretty comfortable with my own company, listening to certain songs for inspiration, coming up with ideas, figuring out where the project is at, and also what I want to do next? Bringing an assistant would be useful of course, if it was someone you connect with on a personal level. But for a personal project, that’s an expensive luxury at the moment.

Walk me through this photo

This was taken while out stalking with a gamekeeper called Stevie. He’d sent me out the previous year with one of his team to burn the heather (which turned into the portrait of Adam, standing on a rock with the flame thrower). So now he was going to show me how they go about getting their quota of deer each winter. After a very tense and delicate approach stalking the animal, he shot and gutted it on the side of a steep snow-covered hill. He then insisted I drag it back down to the Land Rover myself (I think this was a bit of a test to see how willing I was to get blood on my soft urbanite hands). After a few slips and tumbles down the hill, we both loaded it onto the bull-bars of the 4x4, which is when the blood starting pouring through its nose onto the snow as you see in the photo. I suppose looking at the semiotics of this shot, you see the imprint of man and machine across pristine snow and the blood of an animal that was raised for a purpose. It probably encapsulates a lot about the project.

Mat Hay’s Heather Burn will be on show in Sydney at the Paddington Reservoir Gardens, Eastern Chamber, as part of the group exhibit Subterranean, during Head On Photo Festival from 5-28th May.

The exhibition preview and ‘meet the artists’ is 2-4pm on Saturday 6th May

Interview by Aidan Wondracz for AHB

Receive a postcard from us sign up