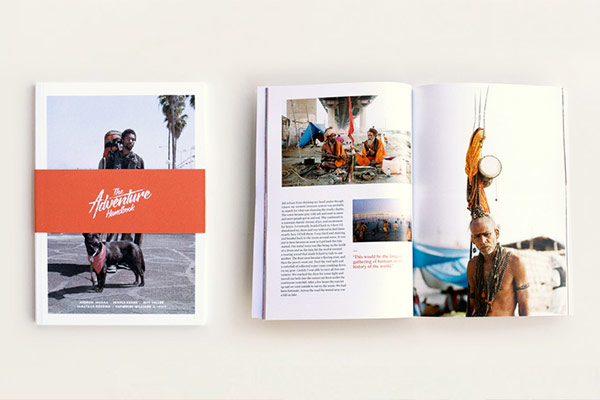

Goats climb trees, the donkeys outnumber the cars and the mountains are etched so as to turn the landscape into a great sunken jaw. I didn’t feel the need to visit before; my prediction of a land that didn’t change, a land that stood still shrouded in Berber mystery and tradition was only half right and it made me question my mind’s eye.

Visiting Morrocco is like slipping into the ancient parchment of an ancient religious text… and the beauty of an ancient text is that the pages don’t change, the paper might curl and pictures might fade, but the fundamental plot remains.

Barely opening my eyes through the excruciating heat, finding our Rhiad accommodation has now become a cinematic memory where everything played out like a film from the 1960s. The streets scattering to fit just one stream of traffic in, scooters driving a little too close to pedestrians- clipping elbows, blind orphaned kittens eating fish heads in the gutter… somehow collaborated to what I saw as a street play just for me.

As if purposefully rebelling the cluttered universe of the streets, the Rhiad was a simple and tranquil space, offset with dark wood, orange stone and strange artefacts. The conundrum of this Rhiad and others was that it lacked any form of porch or driveway. No room. So you could have one foot back in the chaos and one foot in the calm at the same time if you wanted to. Sonically, the children playing in the streets, loose chickens running around the local market contributed to a sound that kept me- eyes aglow- awake during the night. Somehow I sleep better like this, with life with all is noise just a hands reach away, and many nights I slipped back into the streets like a platform video game.

Visiting Morrocco is like slipping into the ancient parchment of an ancient religious text… and the beauty of an ancient text is that the pages don’t change, the paper might curl and pictures might fade, but the fundamental plot remains.

So there we were, on some sort of surreal mountain safari in a taxi with no choice but to keep going towards the South. We flew from town to town on this lost highway, away from the commercial hotels to cattle being herded through crowds and markets on the roadside selling rugs and tagines. Chwiter, Ait Ourir, Touama, Ait Barka. The dry sand piles of solidified rock mass made foreboding shapes along the horizon. The further South we journeyed, the car coiled around around the snaked mountain edges at increasingly acute angles at terrifying height and altitude. After it was too much to bear, I shut my eyes, only to open them to a vision where I couldn’t see the road. A passing truck had blown thick white dust on the road over the taxi, causing us to stop for safety.

Witnessing the commune Ighrem N’Ougdal, it was hard to imagine that people lived there. Stark against the parched landscape, seemingly empty houses scaled frightening heights and we drove on to similar spots Taynmel N’Ogouim, Tisselday, Adighane. Apparently we had reached the holy grail of spirituality, at least for the taxi driver, with a visit to Aït Ben Haddou, a large Ksar (an Arabic term close to castle) which contained a collection of Kasbahs. Magic hour played upon its orange stone streets, as we walked to the summit to admire the stark, mountainous view.

Apparently we had reached the holy grail of spirituality, at least for the taxi driver…

With night falling, we became concerned for the road and our journey home. Our eyes were glad of the twilight rest from the glare, though I wasn’t alone in taking some sharp intakes of breath when the taxi curved round the mountain corners.

Our driver said he was tired and asked me to drive. He had been driving for ten hours and five hundred kilometres with only one break. He’d kept from us the length of the journey but I knew this came from a place of plight not ill will; four million people in Morocco live below the national poverty line, so it’s hard not to tread the humble ground and go along with what the natural local assumption seemed to label us as ‘wealthy tourist’. For all its dry heat, we had seen some startling shades of natural colour today and overwhelming terrain. Our taxi scaled the mountains heading for the city lights, into a night that seemed endless if not for its punch-holed stars.

Receive a postcard from us sign up