Cuba has always held a certain mystery for me. Reading about the island, I was fascinated by the regime’s defiant anti-imperialist stance even in the face of a punitive trade embargo. I was impressed by the country’s commitment to social justice and humanitarian aid yet I was (and still am) critical of the way Cuba is governed with the brothers Castro acting as de facto dictators. Cuba is an island of contrasts; the cacophony of the city at night is cut through with the brittle notes of the tres Cubano, impeccable colonial buildings sit adjacent to crumbling houses. Generations of settling, invasion, embargoes and Revolución have left their unique and indelible mark on the island and its people. It is the history, the intoxicating music and the incredible island landscapes that finally drew us there in December last year.

Ours was a bare-bones itinerary, beginning in Havana then lazily working our way west into the country via the tobacco growing regions near Viñales, along the south of the island before forking back up through Santa Clara and returning to Havana via the beaches near Varadero; we would save the rest of the island for another trip. We had arranged to stay in a few casas particulares along the way – state-approved homestays where Cubans with spare rooms can put up tourists for a few CUCs (Cuban Convertible Peso) a night. The government had recently relaxed regulation surrounding who could run a casa particular, meaning a large number of enterprising Cubans now offer places to stay or have a meal.

The mile-a-minute conversation from our driver Escocia? Muy frio alli, no? was blocked out by the noise of a street party celebrating the return of Cuban doctors from the Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone.

The reek of petrol fumes filled the cab, the window handle hadn’t worked in ages and offered no relief. Our driver pointed out landmarks, punctuating each sentence with a blast of his horn and a “Hombre! Que haces!” at whoever was in front of him. We arrived at our accommodation for the night, not before driving past the Capitolio building, shrouded in a shabby scaffolding, the streets still pock marked with bullet holes.

We spent the next few days criss-crossing Havana, hitching rides for a few coins from whichever jalopy looked the least likely to collapse on route. My favourite view came from standing at one end of the Malecón, looking along at the waves breaking on the ruined wall with the city sprawled out ahead. In Havana Vieja, the old part of town, we accept an invite into a crowded apartment where we looked out onto the street. Below barefoot kids played football, dodging Soviet-era cars. All the while we were careful not to lean on the balcony rail, which had rusted through decades before.

Later we got lost in the Necropolis, roaming through the rows of impeccable marble mausoleums and arrays of well-tended plots. For a few CUCs the groundskeeper gave us a tour. Our last evening in Havana was spent at the Hotel Nacional de Cuba, an imposing building overlooking the Malecón where we paid over the odds for a mojito to sit with well-heeled tourists and watched souped-up Ladas race down the boulevard.

The next day we left Havana early, fleeing angry taxi drivers all jockeying for our business. We headed west to the Pinar del Río Province of Cuba and the rural town of Viñales. The autopista was deserted, save for a few people waving fistfuls of pesos from the hard shoulder, looking for a ride. The driver ignored them and picked his way through the cracks in the road with a skillful nonchalance.

Viñales is an intriguing mixture of tropical lusciousness and pastoral idyll, surrounded by extra-terrestrial mogote rock formations.

Viñales is an intriguing mixture of tropical lusciousness and pastoral idyll, surrounded by extra-terrestrial mogote rock formations. Our casa overlooked a tobacco plantation, we ate breakfast with a treefrog and a Zunzuncito (the world’s smallest hummingbird) for company.

The number of tourists in Viñales is testament to the number of things to do here. You can disappear underground in the Santo Tomas caves, a vast subterranean network whose cathedral-like rooms once hid revolutionaries; you can stroll through the farmlands, swim in the lakes; have a go at rolling a cigar and dodge the tyres rolled through the streets by the farmers’ kids, who eye you suspiciously as you pass.

From Viñales we headed east towards the town of Cienfuegos, an erratic journey which needed three separate vehicles – the first was arranged by the owners of our casa in Viñales,“Claro es comodo!” They took us near to Havana where we swapped cars, “Claro es seguro!” – which broke down near Giron. The third (I’d stopped enquiring about the cars by this point) was to take us the rest of the way, picking up a courteous policeman en route. You can’t predict the Cuban way of doing things, just go with the flow. Large parts of the road were single file, one lane cleared to allow miles and miles of rice to be dried in the sun. Workmen chased the goats away. In Cienfuegos, we dropped our things off at casa Emilo and marvelled at the brightly coloured colonial buildings in Parque Jose Marti. We walked along the promenade, past the children fishing and leather-faced old men drinking rum from cartons in the street.

Young people spilled out onto the road from a noisy club. Pedal taxis circled, their kid drivers hollering their buen precios. At the end of the walk at Punta Gorda, a well-dressed waiter sidled up to us, playing it Bogart, offering us the best mojitos in Cuba or our money back. He kept his word and our money, they were fantastic.

From Cienfuegos we visited the beach at Rancho Luna. Hiring snorkeling equipment we spent a few hours bobbing face down in the aquamarine sea, admiring the coral whilst trying not to let the swell of the sea press us against the sea urchins below. After the beach we drove the dusty road to the El Nicho park.

Next we headed to the UNESCO-listed city of Trinidad. The markets here have everything; one guy swept back a curtain to reveal contraband coral jewellery, illegal to take out of Cuba. Despite the high tourist throughput, walking these streets on a balmy afternoon, the doors and windows thrown open in the languid heat, can still afford an authentic glimpse into Trinidadian life.

Sounds of a rowdy game of dominos, the pieces slammed down onto a rickety table, were drowned out by a telenovela blaring from a nearby television set. A horse passed, pulling a cart stuffed with blackened plantain. A climb up the rickety staircase of the Municipal museum yielded fantastic views and plenty of graffiti. The earliest I found was scrawled by Xavi, in 1996.

After Trinidad we headed to Santa Clara, right in the centre of Cuba and the farthest east we would make it this trip. The main attraction here is the Che Guevara Mausoleum and we arrived just early enough to read the inscription of Guevera’s farewell letter to Castro before the first tour busses arrive. The mausoleum is incredibly popular, with hundreds of thousands of visitors every year. The loud groups of people, selfie-sticks in hand, feel incongruous with reverence, so we didn’t hang around.

“Yo no fumo” is a good phrase to learn, unless you want a suitcase full of Monte Cristos to take back with you.

Walking back to Parque Vidal, a boy with a barn owl tied to his wrist cycled by. A digger bounced past, two scowling workmen in its front scoop. Walking around Cuba is fantastic for little scenes like these. Cuba is incredibly safe to walk around in, however you will be hassled for taxis, restaurants and cigars a lot. “Yo no fumo” is a good phrase to learn, unless you want a suitcase full of Monte Cristos to take back with you.

Our last stop before Havana and our flight home was the beach resort of Varadero. It is possible to come to Cuba and only see Varadero – and many sadly do. Its hotels and 20 kilometers of pristine white beaches provide the all-inclusive decadence you could ever need. A million foreigners pass through every year – it is not an underestimation to say Varadero is crucial to the Cuban economy.

A stay here almost feels like cheating when compared to the perpetual hustle of the rest of Cuba, though after nearly two weeks of walking for hours each day surrounded by the incessant refrain of Cuban life, a few days’ relaxation (and unlimited piña coladas) were welcome.

I swear the sea there, iridescent in the afternoon sun, has a restorative quality like nowhere else on earth. We headed back to Havana recharged yet sad, knowing we would be returning home soon.

Our final night in Havana was spent in an art deco flat in the Vedado neighbourhood with our cheerful host Mercedes, the building secured with heavy wrought iron doors, the street lined with wildly overgrown trees. The last of our money went a long way in a peso bar off the Avenida Paseo, where we watched teenagers come up to try and buy beer.

Returning to Jose Mari airport and our flight home, we were already thinking about when we’d return and explore the east of island… With the recent diplomatic thawing between the USA and Cuba it is clear that with more foreign investment Cuba will undergo significant changes in the near future – a second Período Especial perhaps.

My advice: learn some Spanish, take a month off, and let yourself get lost in the atmosphere of this incredible place.

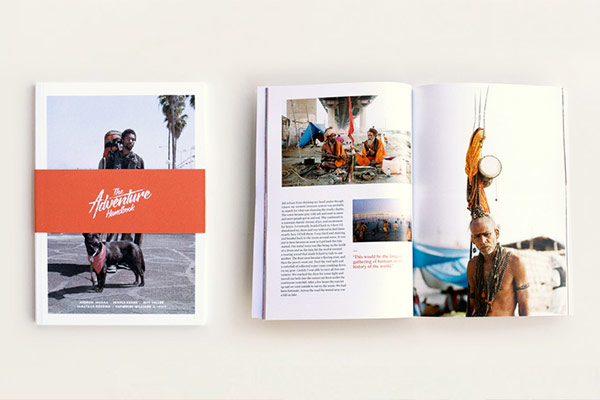

Words and images by Fraser Douglas. Gear: Pentax P50 / Portra 400VC

Receive a postcard from us sign up